Introduction

A number of charities enter into annuity contracts as one of the services they provide to potential donors under their planned giving programs. A few charities have been issuing annuities for more than 50 years.

Many senior citizens, particularly widows, seek assistance in the administration of their financial affairs because they recognize that as they get older, it may become ever more difficult to look after their own affairs. They may also wish to make provision for the distribution of their estates while they are still capable of dealing with such matters competently.

Some charities have responded to this situation by adopting gift annuity programs which are designed to meet these needs while at the same time recognizing that any funds that remain will be available to the charity since generally, under such arrangements, the amount contributed is more than the amount that would be needed to fund the required annuity. In some instances the annual annuity payment is also less than the annual investment income earned on the funds which were paid to the charity for the annuity. In each case there is a potential benefit for the charity.

Donors elect to acquire these annuities because they want a particular charity to be the residual beneficiary of a portion, or all, of their estates. To achieve this, some or all of the donor’s property is turned over to the charity on condition that the charity provide the donor with a specific life annuity. The charity then invests the donor’s funds with the purpose of paying the annuity out of resulting investment income and the annuity provides an assured flow of income for the life of the donor. Most donors enter into such an arrangement when they have disposed of their homes and have moved to a senior citizens’ home where their physical needs will be met.

Charities take the position that they are not competing with commercial life insurers when they undertake to provide annuities. They point out that the consideration they receive is always in excess of the amount that would be required to fund an annuity offered by a commercial life insurer. Thus, more money is available to the charity than would be available if the annuity were purchased from a commercial insurer. Charities justify their involvement in annuities on the grounds that they are assisting their donors both to manage their personal financial affairs and to provide financial assistance to a charity they support. They argue, therefore that they are not in the annuity business; they are simply providing financial counselling to their supporting constituency.

Taxation of Annuities

Charities have relied on Revenue Canada’s Interpretation Bulletin 111R to determine the portion of each annuity payment that could be considered to be a return of capital. These rules apply to any annuity issued by a charity prior to December 2, 1982 where annuity payments had commenced before that date. Under these rules the entire amount of an annuity payment is included in income and the annuitant is entitled to a deduction for the portion of the annuity payment determined, by prescribed rules, to be a return of capital. That amount is determined by applying the ratio of the amount paid for the annuity (including the gift portion) to the total amount of annuity payments expected to be paid under the annuity contract. Revenue Canada specified the number of payments that would be expected to be made under life annuities issued by charities taking into account the age of the annuitant at the time the annuity was issued and the sex of the annuitant. Since the amount paid to charities for annuities in each case would be greater than the amount that would be required for an identical annuity issued by a commercial life insurer, the capital element would be a significant portion of the annuity payment and, in some cases, the entire payment. These regulations allowed a significant portion, or all, of the investment income to accumulate for the benefit of the charity and the charity, being exempt from tax, obtained the full benefit of such investment income. Revenue Canada also recognized a portion of the payment by the annuitant as an immediate gift to the charity to the extent that the amount contributed exceeded the expected payments.

The rules in the Income Tax Act regarding taxation of the income component of annuity payments changed significantly for annuities issued after December 1, 1982. The former rules, which allowed a deduction for a constant amount as a return of capital, do not apply to an annuity issued after December 1, 1982 unless the annuity contract qualifies as a “prescribed annuity contract”. A prescribed annuity contract is an annuity issued by a life insurer or other financial institution listed in the Income Tax Regulations that meets certain conditions. Since charities are not included in this list, annuities issued by charities would not qualify as prescribed annuity contracts under the present law. Under the rules applicable to non-prescribed annuities issued after December 1, 1982, annuitants are subject to tax on any income that is considered to have accrued to them under the annuity.

Generally, an individual will be required to include in income, on the third anniversary of the contract and every third year thereafter, an amount which is considered to be the income accrued for the benefit of the annuitant under the contract to the end of that period less any amounts previously included in income. The amount of income which is considered to have accrued might best be described as:the amount determined by applying an interest factor (i.e., the rate assumed in determining the consideration for the annuity) to the amount considered to be held by the issuer in connection with the annuity during the period for which the accrued income is being determined. In each of the two intervening years the annuitant is subject to tax on amounts received to the extent that such

amounts represent accrued untaxed income at the end of such year. Under this system the annuitant is only considered to have received a return of capital when the aggregate of annuity payments exceeds the income that is considered to have accrued. Where annuity payments exceed both accrued income and the amount paid to acquire the annuity such excess is also included in income. This situation would arise where the annuitant lived longer than expected.

The interest factor for an annuity issued by a charity should be relatively low provided that the entire amount contributed for the annuity, including the gift element, is taken into account when it is determined. Where the amount contributed is equal to, or greater than, the expected annuity payments the interest factor should be zero.

Where the annuitant so elects, income accruing under an annuity contract may be taxed on an accrual basis each year rather than on a received basis for two years with the accrual basis applying only to the third year. The annuitant can adopt this method simply by notifying the issuer of the annuity in writing. Such an election may be made to permit the annuitant to take advantage of the $1,000 annual interest and dividend deduction.

The Income Tax Regulations require those who are licensed or otherwise authorized under a law of Canada or of a province to issue annuity contracts to report annually on form T4A Supplementary the amounts that must be included in the income of their annuitants. It would appear that a charity would be required to comply with these provisions if it had been formed by a special act of the federal Parliament or a provincial legislature with the power to issue annuities. Other charities who issue annuities would not appear to be subject to these reporting requirements.

The Department of Finance has agreed to consider an amendment to the Income Tax Regulations to include charities in the list of organizations qualified to issue prescribed annuity contracts. It would be expected that before such action is taken, the Department would have to be satisfied that the charities issuing annuity contracts were authorized to do so, i.e., that they have the corporate power to issue annuities and are properly licensed to do so.

Power to Issue Annuities

A few charities incorporated many years ago by private acts of Parliament have the corporate power to issue annuity contracts but it is unlikely that any charity incorporated by letters patent, whether federally or provincially, would be authorized to enter into annuity contracts.

The primary role of the insurance regulatory authorities is to ensure that the issuer of contracts of insurance, including annuities, is able to meet its obligations under such contracts. There would appear to be no justification for excluding a charity from such regulation when it issues annuity contracts.

The Canadian and British Insurance Companies Act and the provincial insurance acts regard the provision of annuities as the business of insurance companies. In fact, in Ontario, a corporation that enters into a contract of insurance, including an annuity contract, is “deemed to be an insurer carrying on business in Ontario”.

To issue a contract of insurance, including an annuity contract, a corporation must be registered under the applicable insurance act. Since neither the Canadian and British Insurance Companies Act nor the provincial acts contemplate the registration of charities to permit them to issue annuity contracts, it would appear that they may actually be precluded from issuing such contracts, although it should be noted that the insurance acts do provide for the registration of certain not-for-profit corporations that provide insurance and annuities to members. These are corporations formed for social and fraternal purposes. Thus the insurance acts do contemplate the regulation of non-profit corporations that issue annuities and provide insurance to members even though such activities are incidental to their principal activity.

It has been argued that charities which issue annuity contracts are not subject to the registration and other requirements of the insurance acts because they are not carrying on an insurance business. This argument points out that the consideration received by the charity is not commercial consideration for the issue of the annuity because the amount paid includes a gift element. However, as we shall see, the charitable purposes could be achieved by having a life insurer rather than the charity provide the annuity. Under these circumstances, the charity’s benefactor would receive more favourable tax treatment and the charity could use the gift portion immediately in its charitable work. Furthermore, the benefit to the charity could only exceed the gift portion in cases where the charity issued the annuity and realized a profit equivalent to the profit that is assumed to be earned by the life insurer (i.e., only when the yield obtained by the charity on the investment of funds equal to the reserve that would be held by the life insurer for such annuity was greater than the yield assumed by the life insurer in pricing the annuity and such increased yield was either enhanced by favourable mortality experience or, at least, was not totally offset by unfavourable mortality experience). In these circumstances, it is clear that the charity, by choosing to issue its own annuities, would be seeking to enhance the benefit to itself by realizing the life insurer’s profit. Thus it would appear that the charity would be carrying on its annuity business for profit and would be competing with commercial life insurers for this business.

The amount received by the charity could be viewed as having two components: a contingent gift component and an amount equivalent to the commercial consideration for the annuity to be provided by the charity. The gift portion is held by the charity as a contingency reserve which may be drawn upon in the event of unfavourable mortality or investment experience. Thus the gift is contingent until the annuitant dies and may be viewed as the equivalent of the capital which is normally held by a life insurer in connection with the underwriting of annuity risks.

The separation of the payment into its two components is comparable to the separation of the consideration paid to attend a fund-raising dinner sponsored by a charity. IT-110R provides that the amount paid to attend a fund-raising dinner has two components: the amount paid for the dinner provided (i.e., its fair market value) and the gift component. Applying this same approach to the amount paid to a charity where an annuity is to be issued would permit the identification of the consideration for the annuity and permit the computation of the income or loss from the charity’s “annuity business”.

We understand that if a charity undertook an annuity contract without the corporate power to do so and later defaulted on the annuity payments, the directors of the charity who authorized or acquiesced in the issue of the contract could be personally liable for the payments. In these circumstances the charity could also be subject to the penalties provided in the applicable insurance act and risks having its letters patent revoked. Charities which are authorized to issue annuities under private federal acts could be subject to the penalties provided in the Canadian and British Insurance Companies Act for those entering into insurance contracts without being registered under the Act. However, since these charities have been authorized by an act of Parliament and have been entering into annuity contracts for many years, it is highly unlikely that such penalties would be applied.

Furthermore, for income tax purposes, charities which carry on an extensive annuity program could be regarded as carrying on a business. Such a business would appear to be a “related business” as that term is defined in the Income Tax Act. Therefore, where there was a clearly identifiable gift element in the consideration paid to the charity for an annuity it issues it is unlikely that the annuity business could be regarded as an “unrelated business”.

Gift Annuity Plans Offered by Financial Institutions

Some financial institutions offer a gift annuity plan package as a service to charities. Under one such plan, the “premium” for the annuity is paid into a trust to provide the funds out of which the annuity is to be paid. The arrangement is established by an agreement to which the charity, the charity’s benefactor and a trust company (as trustee) are the parties. While under the agreement the charity is described as the “issue of the annuity” all annuity payments are made by the trustee. The agreement provides for an annuity for “the life” of the annuitant to be paid first out of income, with the remainder, if any, out of capital. Under the arrangement, any income of the trust which is not paid to the annuitant is added to the capital of the trust. The agreement provides that the annuity cease on the death of the annuitant or when the trust fund is exhausted, whichever occurs first. Any funds remaining in the trust fund on the death of the annuitant are paid to the charity. The annuity paid under the plan is said to be eligible for the capital element deduction on the basis of Revenue Canada’s ITlllR.

Under this arrangement it is not entirely clear whether the charity is guaranteeing the annuity payments or is simply the residual beneficiary of a trust established by the benefactor since the benefactor pays the capital sum directly to the trustee, the benefactor provides directions to the trustee with respect to the investment of the funds in the trust, and the annuity is paid to the benefactor by the trustee. Furthermore, the charity would not appear to be required to provide any funds to pay the annuity since the return on investment is not guaranteed and annuity payments cease when the trust fund is exhausted. Thus, in this case, the charity would not appear to be required to use any of its charitable resources under any circumstances to supplement annuity payments.

Notwithstanding the agreement which describes the charity as the issuer of the annuity, it would appear that the charity is not, in fact, issuing an annuity and is not providing any guarantees. Thus the lack of corporate power to issue annuities should not be an impediment to the use of this plan and it would appear that the insurance acts would not be applicable to such plans.

If the trust were to be considered to be settled by the benefactor it would appear that all the income earned on the funds in the trust, and any net capital gains realized on the disposition of trust property, would be taxed annually in the hands of the benefactor even where such income and net gains exceeded the annual annuity payments received by the benefactor. This treatment under the Income Tax Act would apply if the benefactor were considered to be both the settlor and a capital beneficiary of the trust. Under these circumstances, the benefactor would not be entitled to treat any portion of the payment as a gift to the charity.

If the charity were considered to be primarily liable for paying the annuity and thus considered to have received the payment from the benefactor and as having settled the trust, the annuity would not be a prescribed annuity. Even if the rules were to be amended to include charities in the list of organizations which can issue prescribed annuities, it is unlikely that an annuity issued under this plan would qualify since it is neither for a fixed term nor for the life of the annuitant. Thus, as previously noted, the income considered to be accruing to the annuitant would be taxed in the hands of the annuitant. To the extent that the income, including net taxable capital gains of the trust for a year, was not paid out to the annuitant, it would be taxed in the trust at the top marginal rates applicable to individuals. Under this arrangement, Revenue Canada’s IT-Ill R indicates the gift element of the payment to the benefactor would not qualify as a charitable gift unless the payment exceeded the aggregate of all annuity payments expected under the arrangement.

Gift Annuity Plans Where Annuity is Provided by Life Insurer Under some gift annuity plans, the charity arranges for a life annuity to be issued by a life insurer. Under this plan, the excess of the amount contributed to the charity over the amount paid to the life insurer for the annuity would be an immediate gift to the charity and the charity could provide a tax receipt to the donor for such gift. To qualify for the favourable tax treatment available for “prescribed annuities” the donor would have to be the annuitant under the annuity contract but provided that the annuity was an immediate annuity and otherwise qualified it would be a “prescribed annuity”. Under these circumstances, each annuity payment to the charity’s benefactor would contain fixed income and capital elements and only the income element would be taxed in the hands of the annuitant.

Some benefactors might opt for an annuity that would be issued for a guaranteed term, say 10 years. Under these circumstances the charity would be named as the beneficiary of the residual annuity payments which would continue for any balance of the 10-year period after the death of the benefactor.

Gift Annuity Plans Where the Charity Provides the Annuity

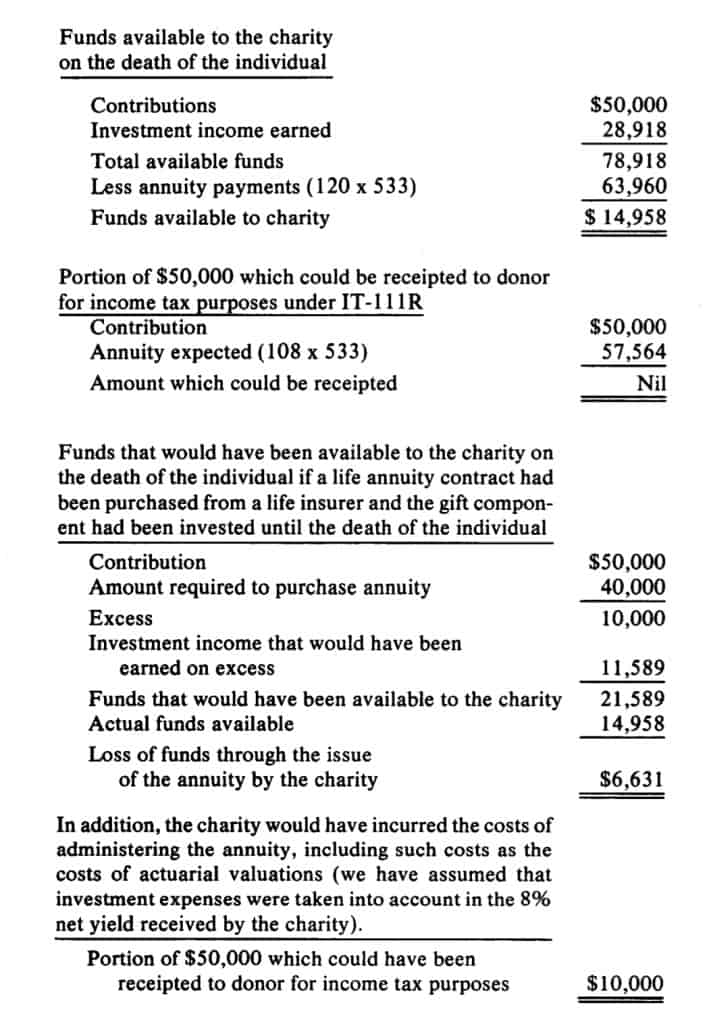

Charities that issue their own annuities would provide the same annuity benefit to the charity’s benefactor. Where this is done, the gift portion of the payment by the benefactor would be held with the normal premium and would be invested throughout the lifetime of the annuitant to ensure that the charity could meet its obligations to the annuitant. While the gift component and the investment income earned thereon would normally be available to the charity on the death of the annuitant, it could be used up by unfavourable mortality or investment experience. However, to the extent that there was favourable mortality or investment experience, the benefit of such favourable experience would be available to the charity under this plan. This amount would be retained by the company where the annuity was issued by a life insurer. However, if the charity purchased the annuity from a life insurer the gift portion of the annuity payment would be immediately available to it and could not be lost through unfavourable mortality or investment experience. On the other hand, the charity would not benefit from the favourable mortality experience if the annuitant died early. If a charity were to analyze its annuity program and segregate the portion of the annuity payments that could be identified as an “upfront gift” (by using the lowest premium which could be paid to obtain the annuity from a commercial life insurer) together with the investment income that was earned on such funds while they were held and invested until the annuitant died, the charity might find that it actually loses money by undertaking the annuity risk. The following example will highlight the potential loss to the charity that would arise from adverse mortality experience.

Assumptions

(I )The amount contributed to the charity by a donor was $50,000 and the donor required a monthly annuity for life of $533.

( 2)The annuity could have been purchased from a life insurer for $40,000 on the basis of a life expectancy of nine years. In pricing the annuity the life insurer assumed an eight per cent return on investment earnings.

(3)The charity provided the annuity and the individual then lived for 10 years.

(4)Funds received and invested by the charity as a result of the annuity produced an average annual net yield of eight per cent.

(See image)

It can be seen from this example that the amount available to the charity would be reduced by unfavourable mortality experience. It should also be noted that the gift component of$10,000 could be receipted if the annuity was issued by a life insurer. Where the charity issues the annuity, IT-111R indicates that no amount can be identified as a gift component. While it might be possible to

realize favourable mortality experience in an individual situation, it is unlikely that the whole portfolio of annuities outstanding at a particular time would consistently produce favourable experience. Furthermore, the charity might not be able to realize the net investment income which is inherent in the annuity premium charged by a life insurer.

It appears that a life insurer can assume the mortality risk under annuity contracts and still offer very competitive rates for the following reasons:

(1) Life insurers who issue annuity contracts are able to hedge their mortality risk through the issue of life insurance contracts. Unfavourable mortality experience to a life insurer under an annuity contract would be favourable experience under a life insurance contract, i.e., if an annuitant lives longer than actuarily expected, the life insurer loses, whereas if the insured under a life insurance policy lives longer than expected the life insurer wins (collects more premiums and more investment income). Since a life insurer holds many annuity and life insurance contracts, unfavourable mortality experience on annuity contracts would generally be offset by favourable experience on life insurance contracts.

(2) Because of the volume of business done by a life insurer it has access to very large pools of capital and can frequently obtain a higher rate of return on its investments than that which could be obtained by an investor who has a small pool of capital. The life insurer with its large pool of capital can absorb investment losses on individual investments which could be disastrous to a charity.

(3) The life insurer, because of its volume, can handle the administrative work related to its annuities with sophisticated computer equipment and thereby reduce the overall unit costs of administration compared to those which would be incurred by the charity.

It would be unlikely that a charity could consistently profit from underwriting annuities and the prospect of such profit in rare instances would not appear to justify the risk of adverse mortality and investment experience. There are a number of additional points that should be considered:

( 1) Where a charity enters into an annuity contract the amount contributed by the annuitant must be applied to a specific use and therefore would not be available to be used by the charity for expenditures on its charitable activities, i.e., the funds are given to the charity to be invested and used to provide annuity income for the annuitant. The annuitant expects that the amount contributed to the charity, together with investment income thereon, will be more than sufficient to make the required annuity payments. The funds remaining at the death of the individual are expected to be available to the charity for carrying on its charitable activities. This arrangement would require that the amount contributed by the individual be excluded from the charity’s operating income and the charity would appear to be required to account for such amount and the income thereon as trust funds, separate from all other funds of the charity until the death of the annuitant.

(2) Religious charities appear to be the principal users of gift annuity programs.

It seems extremely possible that the majority of the benefactors of religious charities might fall into a preferred risk category for insurance purposes (e.g., non-smokers) and thus might be expected to live longer than members of the general community. This would increase the risk of adverse mortality experience.

( 3) Where a charity enters into an annuity contract the possibility always exists that the annuitant may live considerably longer than his or her actuarily determined life expectancy. Under these circumstances, annuity payments may exceed the payment made by the annuitant to acquire the annuity and all of the investment income earned on such funds. The charity would then have to use other resources to maintain the annuity payments. Yet, since all of the resources of a charity (including any income realized on the investment offunds arising from the annuity program) must be held in trust for its charitable purposes, there is some doubt that the charity could properly use its charitable resources for this purpose.

( 4) The charity would be able to obtain more favourable tax treatment for the benefactor by purchasing the annuity from a commercial life insurer. If the charity is prepared to forego this benefit in order to seek an underwriting profit then it would appear to be carrying on an insurance business for profit. This could have the previously discussed adverse consequences.

(5) Where a charity has an active gift annuity program, it may be possible to arrange for favourable annuity rates with a commercial life insurer through the use of a group annuity policy. The commission rates applicable to group annuity policies should be considerably less than commission rates applicable to individual annuities.

Conclusions

All charities with gift annuity programs under which they issue annuities should review these programs and identify the portion of the contribution to the charity that arises from the initial gift and the investment income earned thereon. Such an analysis over the longer term may demonstrate that the charity would be better off to arrange to have its annuity contracts issued by a life insurer on a competitive basis so as to benefit from the initial gift without the risk of losing any portion of it through adverse mortality or investment experience. Should the charity reach such a conclusion, it should take steps to change its annuity program and make arrangements with a commercial life insurer to provide annuities. Charities should also review any annuity plans that involve the use of trusts to provide the annuity to ensure that these are being properly dealt with under the income tax rules relating to such trusts.

Charities that are currently issuing annuities who do not, at least, have the corporate power to issue annuities should seriously consider discontinuing the issue of annuities. Charities not currently issuing annuities should decide not to do so.

This paper identifies serious problems in connection with the use of annuities in the planned giving programs of charities. The author sincerely hopes that it will help each individual charity to make appropriate decisions regarding the use of annuities in its particular planned giving program.

R.C. KNECHTEL

Clarkson, Gordon, Chartered Accountants