Policy affects our lives every day. But often, people with vital lived experience aren’t involved in developing, changing, and influencing policy. The Gordon Foundation is working to change that, by creating the space to bring young people and policy experts together so they can create real, long-term change.

At The Gordon Foundation, we have a long history of working with our partners to engage northern and Indigenous young leaders in policy development. We know that northern and Indigenous young people are interested and engaged in policy that has an impact on their lives. However, they often have little say in how public policy is developed and no opportunity to bring their lived experience to the table.

The first Arctic Policy Hackathon, which took place last year in Reykjavik, aimed to change that.

Policy hackathons bring young people with lived experience together to learn, think, and build their policy muscle. The Arctic Policy Hackathon – organized by The Gordon Foundation, the Canadian International Arctic Centre, and the Arctic Mayors’ Forum – saw young leaders from across the circumpolar north address food sovereignty. Drawing on their direct experience and the advice of policy experts, 14 inspiring young people jointly developed policy recommendations to share with governments and stakeholders in their regions.

The policy recommendations examining food sovereignty in the Arctic cover issues ranging from increasing circumpolar trade to addressing the impacts of climate change. The recommendations demonstrate – including to the participants – the value of their lived experience, individually and collectively. As the participants state, their policy proposals “shift the power to communities to dictate their own well-being through food sovereignty and should be a priority in Arctic policy discussions.”

New leaders see how valuable their perspective is and that they can make change happen.

Getting those policy proposals and the young leaders who wrote them into policy discussions and in front of decision-makers is vital. It helps new leaders learn about the policy development process and the impact they can make. They see how valuable their perspective is and that they can make change happen.

The hackathon took place just before the prestigious Arctic Circle Assembly, where the policy recommendations were shared with politicians and decision-makers. Hackathon participants Patricia Johnson-Castle and Harmony Wayner discussed their work during a panel, and the four northern Canadian participants met with Governor General Mary Simon. We are going back to the Arctic Circle Assembly this year, where we will be challenging policy leaders to see what has changed.

Since the hackathon, participant Nolan Qamanirq has appeared at the Arctic Frontiers conference, sharing his perspective on how climate change is the biggest threat to food security. Qamanirq also spoke at the 2023 Land Claims Agreements Coalition conference about getting young people interested in taking up hunting and accessing local foods.

The value here comes from showing the hackathon participants – and others who may want to take part in the future – that they can be part of the policy process, that their experience is valuable, and that they can have an impact.

***

Like Policy Hackathons, Treaty Simulations are intensive, multi-day events. Indigenous emerging leaders are split into three teams representing – usually – an Indigenous Nation, a province or territory, and the Canadian government. After receiving a mandate letter about a specific issue – for example, wildlife management – they prepare positions and negotiate until they reach an agreement. Expert advisors with years of experience in treaty negotiation and implementation share their wisdom throughout the simulation.

Each Treaty Simulation is tailored so that the fictional scenario being negotiated deals with issues that connect the participants to their treaty and community.

Each Treaty Simulation is tailored so that the fictional scenario being negotiated deals with issues that connect the participants to their treaty and community. For example, previous treaties have negotiated a wildlife management plan for a fictional caribou herd. Co-designing a scenario applicable and relatable to those sitting around the table takes policy off the page and into the participants’ lives.

Treaty Simulations came about after The Gordon Foundation was approached by partners and treaty experts who were concerned that young people were not involved in their treaties. Since then, many national and regional simulations have taken place in partnership with organizations including the Land Claims Agreements Coalition and the Dene Nation.

We’ve learned there is a demand for programs that engage young people in policy work. Interest in Treaty Simulations has grown significantly, with demand having tripled in recent years. This has come about organically, through word of mouth.

We prioritize working with Indigenous organizations, but universities, governments, schools, and even libraries have been interested. We are currently working with the Government of the Northwest Territories to trial Treaty Simulations as part of their northern studies program and a new grade 12 curriculum. Tool kits for educators are also being rolled out.

We know Treaty Simulations work only if there is true collaboration with our partners. We provide the structure, materials, and experience of running similar simulations. Partner organizations and treaty experts add the context, richness, and value that help participants build their policy muscle.

That can happen only if they can learn from treaty experts. When speaking to these busy, in-demand people about why they get involved, what comes up, again and again, is that young people need to be engaged in their treaties.

I thought it would be ideal to pass some of that knowledge and some of the skills down to the younger people. It’s a knowledge transfer.

Dave Joe, Yukon Final Agreement negotiator

Dave Joe, an iconic figure and Yukon Final Agreement negotiator, has been involved with Treaty Simulations since the first event back in 2019. “I thought it would be ideal to pass some of that knowledge and some of the skills down to the younger people,” Joe explains. “It’s a knowledge transfer.”

“I want to make sure that there is someone following behind me that’s going to uphold our agreements,” says Lisa Hutton, manager of implementation and negotiations at Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada (CIRNAC) in the Yukon Region and a Treaty Simulation advisor. “They were fought for long and hard by our ancestors before us, and we need to make sure that we’re upholding these agreements as we move forward into future generations.”

I want to make sure that there is someone following behind me that’s going to uphold our agreements.

Lisa Hutton, Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada

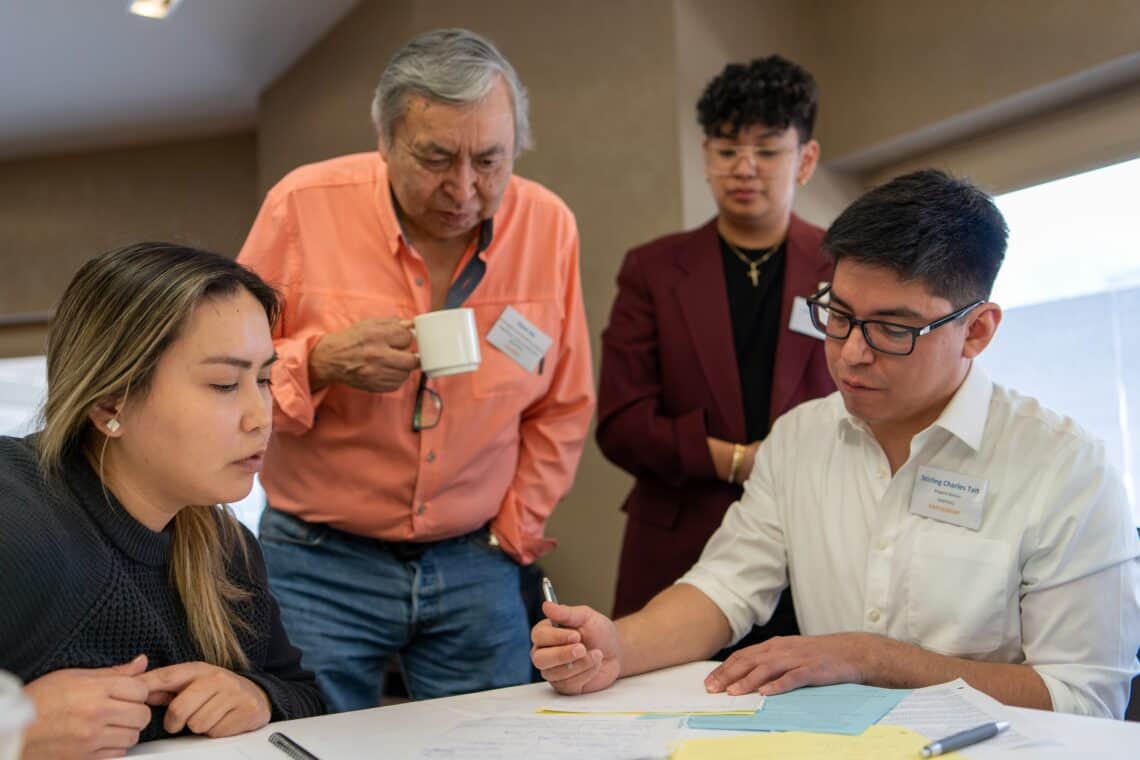

That historical imperative resonates with participants. “The reason I came to the Treaty Simulation was [that] some of my ancestors were part of the Nisga'a Treaty,” explains Stirling Tait, who took part in the fifth National Treaty Simulation, “and I wanted to experience what they experienced.”

While those historic agreements may have been signed decades ago – the Nisga'a Final Agreement came into effect in May 2000 – modern treaty implementation is an ongoing, often painstaking process covering a huge range of policy areas.

The reason I came to the Treaty Simulation was [that] some of my ancestors were part of the Nisga

Stirling Tait, National Treaty Simulation participant'a Treaty, and I wanted to experience what they experienced.

While Treaty Simulations can’t cover everything in a modern treaty, they can show emerging leaders that modern treaty implementation is where important decisions are being made. Once informed, new leaders can develop their opinions on the issues and maybe get involved, using what they’ve learned.

Robin Bradasch, director of governance at CIRNAC Yukon Region, has been involved in treaty negotiations for many years. She sees Treaty Simulations as a good way of encouraging youth to follow careers in negotiation and implementation by “showing that there are so many different applications for negotiation skills and implementation skills.” Simulations, Joe says, show participants how to resolve disputes within the treaty process, teaching “mediation skills, arbitration skills, negotiation skills.”

Participants tell us they improve skills, including negotiation and public speaking, and benefit from intergenerational knowledge transfer and expanded networks. They also increase their knowledge and interest in treaties.

I want to be more involved with the Tłı̨chǫ Government, like when they host their meetings and assemblies.

Mercedes Rabesca, National Treaty Simulation participant

So, what does using this knowledge and skills look like in practice? It could be working in implementation or negotiation for their community or a government organization, being inspired to further their treaty education, or volunteering in their community.

“I want to be more involved with the Tłı̨chǫ Government,” says Mercedes Rabesca, who participated in the fifth National Treaty Simulation, “like when they host their meetings and assemblies.”

I got to pick the brains of a couple of advisers, and I think I might be using some of this knowledge that I’ve gotten in my career.

Stirling Tait

Tait, who works at Gitlaxt'aamiks Village Government, saw professional benefits to taking part. “It’s very informative,” he says of the simulation. “I got to pick the brains of a couple of advisers, and I think I might be using some of this knowledge that I’ve gotten in my career.”

The hope is that a spark is lit that burns long after the Treaty Simulation, giving young people the springboard of confidence and knowledge to see the contribution they can make. They understand that treaties and policies can affect people for generations. Having developed their policy expertise, they can go out into the world and use it.

As a foundation, we can try new approaches that engage young people in policy work. We can take risks. In our current policy hackathon and Treaty Simulation programs, The Gordon Foundation’s role is facilitation and connection – creating the space to bring young people and policy experts together so they can create something special.

More northern and Indigenous people should be involved in policy development and implementation, but they often face systematic barriers to getting involved. There is much work to do with room for different approaches.

By making policy accessible and relatable, people can see its impact on their lives and the value they can bring by getting involved and bringing their lived experience to solutions. By building their policy muscle, they can create real, long-term change, which will benefit all of us.