Financial sustainability does matter. Funding for nonprofit organizations in Canada has reached a critical stage. Large numbers of organizations are constrained, and some are severely threatened by inconsistent and inadequate financing. The causes of this insecurity are many and varied, but the results are potentially changing the face of civil society right across the country. Community benefit organizations, both small and large, face difficult choices, some for the first time and some re-entering a second or third financial crunch. The issue of financial sustainability is once more a powerful driver of change for the nonprofit sector and for communities.

There was a time when financial sustainability could be approached with enthusiasm and optimism: government funding sources were expanding, foundations were flexible, donors were accessible, public consciousness was more community minded, and giving by corporations was growing rapidly. But globalization, information technology, political determination, and insecure financial markets have produced an environment less concerned about community, cause, or culture and more concerned about the integrity of large scale systems and outcomes that suit the needs of funding sources. Nonprofits that are focused on community, cause, or culture now appear to be out of step, out of date, and off the map for support.

Mission-driven organizations, as has been pointed out for decades, have dual sustainability issues. Their first-order task is to achieve and sustain a mission-based purpose, driven by community and human values; their second-order task is to create and sustain an organization of integrity and productivity to carry out the mission. Most nonprofit organizations are born from and driven by a strong first-order purpose, and many believe that if the first-order purpose is successful, the value will be recognized by funders and financial security will follow.

The reality, though, is that the assumption of the evident value of community benefit organizations is gone: all must be proven. Strong and determined funders continue to narrow the scope of first-order work by defining required outcomes ever more tightly, as if communities, causes, or culture were simply a string of measureable indicators. Funders are also more focused on adapting to the new second-order drivers: the sustainability of the funders themselves.

The current high visibility of “social innovation” provides an example of the tensions between the past and present. The classic view that organizations need to achieve a substantial, balanced, and diversified funding base that includes fee-based sales, sustainable long-term fundraising, and continuing support from institutional sources remains true. As institutional support has weakened, particularly in the environmental and arts sectors, some organizations have responded by moving toward social innovation and enterprise solutions to a higher degree than before and have become successful, at least in the immediate term. Will this changing balance provide a basis for long-term financial sustainability?

Large-scale social enterprise and social innovation hold out a promise of success for organizations that have mass appeal and cost-effective solutions for difficult issues, particularly those that can do better by scaling up. Many small and local social enterprises are successful. Social innovations at the micro level continue to provide energy and drive to new solutions for seemingly intractable problems. There remains, however, a continuing need for political and institutional commitment to truly complex community, cause, or cultural issues and problems that are not so appealing and do not yet have readily applicable scalable solutions.

Social innovation has become a focus of many people who either pragmatically observe the trend toward more government cutbacks, support sustainability through new approaches, or support cutbacks in government spending. I support innovative efforts and see a future in which risk-taking and enterprise once again find a front page place in the nonprofit community. I also fear that unproven mega-solutions, fragmentary approach—es, and anecdotal narratives will lead to lots of promise but limited long-term success unless those solutions are actually embedded in communities and supported through public and private citizen participation.

Financial sustainability across the sector is a hard and complicated topic, not answerable in short, punchy bumper stickers or slogans. As the first sector, nonprofits are critical to the fabric of society, and sustainability of this sector is a Canada-wide concern. This issue has deep roots in Canadian culture and the very significant transitions are shaking both the funder community and the sector.

Funders and their changing behaviours

Associational organizations and nonprofit societies have traditionally been drivers of change in North America—the research and development (R&D) engine of community and economic development, human and health development, education, the environment, and so on. The sector’s contribution (with the help of start-up funders) over time has been enormous. Much of that R&D work was later brought to scale by local, provincial, and federal governments that could afford the infrastructure costs. The de facto “social compact” between on-the-ground sector development and institutional and government funders has broken down over the last two decades. (In at least two provinces, provincial governments now refer to the “contracted” sector as part of the “broad public sector” [British Columbia and Ontario]; this is an indication that these provinces do not see sector organizations as partners but rather as aligned contractors.)

In one current transition, some institutions, including sector-based foundations, governments, and social entrepreneurs, appear to want to take over that R&D role through tightly controlled and speculative investments. The rationale for these organizations seems to focus on a belief that the new world order requires transferring the responsibility for R&D from the community sector to larger and more powerful institutions. A result of this transition is that investment outcomes and accountability are more highly controlled, intellectual capital can be controlled and directed, investment funds can be built up over time, substantive financial returns can be achieved, and resources are continuously available with which to speculate on future R&D work. In addition, the very large issue of how knowledge is transferred across a diverse sector is somewhat dictated through elite organizations managing knowledge for the sector’s benefit. This seems to be the emerging focus for “capacity” in the sector and one important element in the loss of financial sustainability in the community, cause, and culture sector.

This factor, I believe, is having a profound effect on financial sustainability of community organizations as funders re-align to new priorities and dis-align from the ongoing program and infrastructure priorities of the past. As this happens, some funders have increasingly taken on a belief that they have superior knowledge and that organizations not aligned with their thinking are non-productive “rent-seekers” out to gain “sales without substance.” I observe this change of alignment and wonder about the limits and downsides. It is difficult for me to envision how the “re-distributive” side of the economy, represented by larger institutional interests, can replace the R&D and longterm service commitments of community-based organizations committed to generosity, reciprocity, and an abundance orientation. This change of investment orientation puts the knowledge and economic clout rooted in the community, cause, and culture sector in direct competition with the institutional investment sector.

As healthcare costs continue to rise disproportionately to everything else in society, community caring is being replaced by mandated individual care and large healthcare infrastructures. This development will further strengthen the hand of large institutions that seek to gain superiority in the social economy. As funders move increasingly toward second-order development (institutional strengthening), they are also seeking to remake funding recipients into delivery agents through contracted and project-based models of funding. In my opinion, mandated individualized funding for care and support will gradually dismantle community-based infrastructures and replace those structures with institutional structures and one-by-one retail care markets.

Unless there is a revival in community-driven research, development, and knowledge transfer, the sector will experience increasing alienation from the funding bodies and speculative investors that are determined to work on institutional priorities rather than on community priorities. Community accountability is already disappearing and being replaced with maximized accountability to external institutions and governments.

looking at ourselves

Given those tectonic shifts in the behaviour of funders, the issues of financial sustainability for sector-driven missions will become even more difficult in the years ahead. It is time for the sector to begin a real dialogue about and amongst itself. This could prove to be painful and slow, so it is time to get started.

The sector has become highly complicated and estranged from itself. For example, historically societies and associations in the nonprofit sector were associational in nature– groups of citizens getting together to do good for a community, a cause, or a cultural imperative. Increasingly the nonprofit “society” has become a vehicle for private initiatives, just another form of incorporation and a way to get privileged access to community assets and wealth and to extract a private wage. These organizations may benefit the larger society in some way, but the driving force is essentially private rather than associational. Another example is the intrusion of governments through the creation of crown societies that act solely for government interests and aggressively compete with truly associational community-based organizations. These intrusions into sector culture are confusing to the public and can destroy the brand value of truly associational organizations.

Sector-based organizations are bound by tradition and law to be trusteeships—financially conservative and oriented toward asset preservation rather than expansion and growth as one would expect from a culture of ownership. In other words, over the life of a newly formed society or association, there is an assumed change of culture from an ownership-driven mentality during the start-up phase (when innovators put in their own resources and sweat equity) to a trustee mentality after institutionalization. This legal and cultural imperative to become conservative needs to be examined and new models of ownership developed across the whole sector.

Funders have sought ever-increasing levels of accountability in return for the funds they provide. This is a pattern arising from both government and charitable foundations. The need for accountability placed on funding recipients by external organizations has not been matched by true accountability in return, i.e., to members of associations and societies or to communities (either local communities or communities of interest). Sector organizations have capitulated to external funders’ demands for operational reporting and measurements of community impact but have not paid the same attention to accountability to members, recipients, and individual or corporate donors. The issue of transferred accountability is symptomatic of a deepening crisis in economic value as well as in core community values.

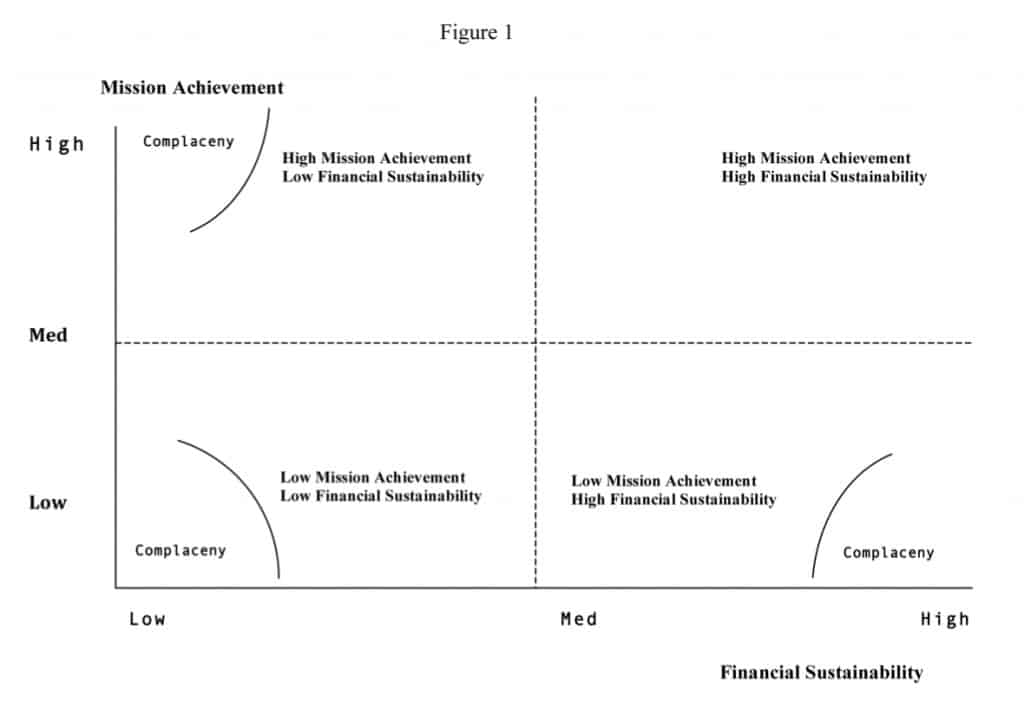

If we construct a matrix of mission achievement and financial sustainability (see Figure 1) for any given organization, it is easy to get confused about the meaning of financial sustainability. Sector-based organizations sometimes believe that the financial sustainability of an organization is more important than the survival of the mission of the organization. This becomes an acute issue as the field has become increasingly crowded with newly formed organizations that share or overlap in time and space with the same mission. It forces organizations to choose or drift toward smaller and smaller niches. These are painful choices, often forced by funders that seek new project vehicles or become enamoured with new methodologies. Seeking organizational survival to the detriment of the long-term mission is ultimately self-defeating. This is an issue that is so pervasive that it seems overwhelming; particularly as more and more private-business-oriented nonprofits enter the market. Refusal to see and address this reality challenges the financial sustainability of all sector organizations.

In my work, I have found that most sector organizations have all kinds of unique assets and abilities that set them apart from others and have acquired a particular brand value in the community. I have also noticed that when representatives of many sector organizations get together in one room there is a tendency to focus on simple statements about common problems like financial sustainability. Further, I notice that truth-telling is an issue as is the fear of risk-taking. Organizations that share or overlap in missions need to find new ways to work together to reduce financial insecurity over time. Ratcheting up anxiety about financial security breeds distrust and dysfunctional competition. Focusing on results for a common mission is a better way to deal with the issue than fighting with each other for scarce resources.

Over and over we hear that nonprofits should become more business-like. Service leadership (rather than business leadership) is what sets many nonprofits apart, making these organizations uniquely valued and supported. But, yes, I believe we do face a problem here. While most nonprofits are more efficient and effective than counterpart private businesses, there is a lingering sense that service leadership is not enough. So what is “being more business-like?” Making profits? Being more market driven? Being more risk oriented? Getting to scale more quickly? Growing through mergers and acquisitions? Holding subsidiaries? Selling bonds in the financial markets? Forming industry groups to lobby? Keeping better minutes and organizing flashier events?

Just what does business-like mean? I believe it is pretty simple—though not easy. I think it means applying a culture of ownership and risk-taking to both service and organizational leadership. Risk-taking is exciting and energizing. Investing is fun and challenging. Making use of business instruments that work in small business and putting those instruments into service for the public benefit can be a difficult but noble driver in the sector. Learning new design strategies from the artists and innovators in our communities is a place to start. The sector can only reassert its place in Canadian society by being assertive on a whole new level and this is one place to start.

I have also noticed that organizations in the sector spend a lot of time differentiating themselves from other organizations. Differentiation is a branding tool that consumes a lot of time. But, in reality, most of what organizations actually do on a day-to-day basis is exactly the same: they hire staff, offer programs, lease or own a building, have telephone systems, have an accounting function, hold board and committee meetings, etc. The somewhat obsessive behaviour around differentiation is about the unique mission and methods rather than about the daily business practices. So why does each organization have to do all of this duplicative stuff? Why do we not have shared business forms for the day-to-day workings and spend our best energies on the really unique aspects of achieving the mission? General refusal across the sector to make these new forms for business effectiveness reveals a kind of intransigence that blurs the brand and increases the level of distrust from funders. In my view, this is an urgent issue about which we need to have a dialogue.

Earlier we spoke about the desire of funders to reduce perceived inefficiencies by forcing recipient organizations into contracted or granted roles focused exclusively on outcomes specifically designed by the funders. Is this a proper role for sector organizations? Perhaps it is a good role in areas where a level of service maturity has been achieved. Becoming a provider of proscribed services is a reduced role for most nonprofits that started out with a unique mission. Drifting into roles that are not self-directed may cause an organization to end up acting like a cash-starved dependent contractor or a utility. This is tough on the sector brand because it reduces out one of the prime functions of the sector—to mobilize and act on behalf of members toward a shared vision and purpose, and to bring associational spirit and technologies to bear on issues of common concern in community, cause, and cultural fields. It may be time to consider making some pacts around how the sector wants to deal with this critical issue.

Funding does matter and so does financing. In looking through scores of Canada Revenue Agency Charity T3010 reports, I am continually struck by the liquid and investment funds held by some groupings of charities. In one 2009 sample of 100 Charities in British Columbia we found: liquid assets of about $83 million; capital assets of $150 million; net equity of over $79 million; and annual revenues of about $350 million. This is not a poverty-driven or crisis situation but it does demonstrate that good business practices in the sector are based on using capital as a risk-mitigation strategy rather than as a lever and basis for long term risk-taking. It also demonstrates, I believe, that collectively we have not yet figured out how to use the financial assets already in place. As part of truthtelling and collective ownership in the sector, this is an issue.

Earlier there was an allusion to sector organizations as “rent-seekers”. I want to explore that concept briefly. The Wikipedia (n.d.) definition of rent-seeking is:

the expenditure of resources attempting to enrich oneself by increasing one’s share of a fixed amount of wealth rather than trying to create wealth. Since resources are expended but no new wealth is created, the net effect of rent-seeking is to reduce the sum of social wealth. (para. 3)

Assuming we can remove the reference to individuals in the definition, we can ask ourselves this question: Is this what sector organizations do? In a time of no growth (or reductions) in the funds available, are sector organizations, through heavy competition and more desperate financial situations, actually reducing overall wealth by draining funds off into unproductive work? Are we trying to gain monopoly control? Is it possible that there is an inadvertent corruption problem? Are collaborative efforts reducing effectiveness and driving up prices but not costs? I don’t think so, and I do not buy the charge of “rent-seeking.” However, it does create an issue for the sector if that is a perception amongst funders.

If that perception is based on the fact that sector workers need pension and insurance programs and competitive wages, or that association executives need competitive salaries, or that sector organizations need vastly improved human resources policies and matching financing, then we have a common issue. As a traditionally under-financed sector, there is a lot of catching up to do and some funders resent or reject the rising pricing caused by the catch-up.

The more important point is that, if the sector is ever perceived as not “trying to create wealth,” then the issue becomes the most critical discussion possible, as the brand is completely dependent on the creation of common capital for common use.

So what needs to change?

I am very heartened by the deeply courageous, innovative, and enterprising spirit I see in many nonprofit organizations, and I believe that is where the future lies. I see the need for wholesale change, starting with our own sector players. Financial sustainability is a function of mission sustainability rather than the sustainability of each organization as each operates today. Do we have the courage to take the risks required? Can we remake organizations so that each community, cause, and culture finds its best and more effective voice, passion, and direction in today’s restricted financial environment? If we cannot change the way our organizations function, how can we expect that funders will change?

I believe it is a tough road but passable and possible. Here are some specifics ideas:

1. Become more ownership driven, and risk and innovation oriented: develop co-operatives, enterprises, and innovation networks as new forms of shared work.

2. Become more collaborative across all of the dimensions of organizational effectiveness.

3. Lead our communities, causes, and cultures though assertive knowledge transfer programs that bring the best of the sector to all parts of Canada and all parts of the sector.

4. Develop common priorities for policy development and change strategies that create capital and wealth for each community, cause, and cultural phenomenon.

5. Develop common funder relationship strategies based on common core social and economic values and measures of success.

6. Develop a common fund and investment strategy for community-based research and development that supports social, health, and economic development for Canadians.

In other areas of Canadian culture, industry groups have developed self-financed organizations and programs for change at local, provincial/territorial, and national levels. It is time our sector did the same thing. I believe that out of the vast diversity of the sector, reflecting the diversity of Canada and the best dreams of Canadians, will arise a shared vision and the potential to once more play the powerful role of generating community responses to community need.

Reference

Wikipedia. (n.d.) Rent-seeking. URL: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rent-seeking

[September 30, 2011].

Tim Beachy is the past CEO of the United Community Services Cooperative, former Vice President of United Way/Centraide Canada, former Executive Director of the Com-munity Social Service Employers Association of BC, Chair of the BC Centre for Non-Profit Management and Sustainability, and holds directorships in several other associations. Tim lives in Langley, BC. Email: tbeachy@telus.net