This article was developed from a presentation to a private seminar for hospitals and universities held in Toronto on December 2, 1992.

Overview

Prior to 1988, tax relief with respect to charitable donations, gifts to the Crown and gifts of certain property was allowed as a deduction in computing a taxpayer’s taxable income for the purposes of the Act.1 For 1988 and thereafter, for individuals (including trusts) other than those who have taken a perpetual vow of poverty as provided for in subsection 110(2), the deductions have now been replaced by a two-tier nonrefundable and nontransferable federal tax credit set out in section 118.1.

Individual Credits

Subsection 118.1(1) provides, in the definition of “total charitable gifts”, that gifts made to the following institutions qualify as charitable gifts:

(a) gifts to a registered charity (as defined in subsection 248(1) which includes charitable organizations and private or public foundations, as defined);

(b) gifts to a registered Canadian amateur athletic association (as defined in subsection 248(1));

(c) gifts to a housing corporation providing low-cost housing that is exempt from tax by virtue of paragraph 149(1)(i);

(d) gifts to a Canadian municipality;2

(e) gifts to the United Nations or one of its agencies;

(t) gifts to a university outside Canada prescribed to be a university the student body of which ordinarily includes students from Canada; or

(g) gifts to a charitable organization outside Canada to which Her Majesty in right of Canada has made a gift during the individual’s taxation year or during the preceding 12 months.

Similarly, gifts made to Her Majesty in right of Canada or Her Majesty in right of a province also qualify as charitable gifts, as do gifts of certain cultural property that are gifted to designated institutions under the Cultural Property

Export and Import Act.

In each year the amount of charitable donations for an individual cannot exceed one-fifth of the individual’s income for that year, although certain gifts to the Crown and gifts of certain cultural property are not subject to the 20-per-cent limitation. Any credits not used in a particular year because of income limitations or because the individual chose not to use them may, subject to limitations, be carried forward for five years. The formula for the deduction of the donation is as set out in subsection 118.1(3). Section 118.92 sets out the order that tax credits (including credits under section 117.1) may be used in computing income tax payable under Part I.

Charitable donations made by a taxpayer cannot be claimed by any other party; however, administratively, Revenue Canada allows donations and the resulting credits to be pooled in the nuclear family. Receipts issued in the name of any of: the taxpayer, a spouse, or dependent children have been accepted by Revenue Canada as donations of the taxpayer or any of these.

Receipts must be obtained as evidence of the gifts and such receipts must comply with sections 3500 and 3501 of Part XXXV of the regulations to the Act.

Corporate Deductions

Subsection 110.1(1) provides for the deduction from taxable income of the amount of charitable contributions made by corporations (as opposed to individuals who are entitled to deduct credits from tax otherwise payable). Paragraph 110.1(1)(c) provides for deduction of gifts that are made to certain institutions noted therein (essentially the same institutions to which an individual may make a donation and receive a credit). Similarly, a corporation is restricted from deducting charitable donations in any fiscal year in an amount in excess of 20 per cent of income but may carry forward such deductions for up to five years, subject to limitations. If an individual de facto controls a corporation, for example, then both the individual and the corporation may make donations and effectively double the limits. As for individuals, there is no 20-per-cent limitation on donations to the Crown and donations of certain cultural property. Again, the rules governing corporations, gifts of capital property, gifts to the Crown and gifts of cultural property are similar to those applicable to individuals.

Donations

For a transfer of property to be considered a gift for purposes of sections 110.1 and 118.1 there must be a voluntary transfer of property without any consideration passing to the donor and without any expectation of benefit to be derived by the donor from the gift and the gift must be made without conditions. In

Interpretation Bulletin IT-110R2, Information Circular 80-10R and in numerous Technical Interpretations, Revenue Canada has set out its views as to what constitutes a donation. For example, Revenue Canada has considered, in a Technical Interpretation dated October 1, 1990, whether the provision to a charity of reduced rental for a property would be considered a gift of property. It was determined that reduced rental would not be a voluntary transfer of property; however, if fair market rental were charged and the rental income was gifted back to the charity, then there would be a transfer of property to the charity, provided that the recipient of the rental (the donor) was not contractually bound to make the donation pursuant to the provisions of the lease. Similarly, future breeding rights were held to be property as that term is defined in subsection 248 (1) for which a charitable receipt may be issued3 as were restrictive covenants in land donated to Her Majesty or a charity.4 There is also much jurisprudence dealing with the issue of whether consideration has been received for a donation and therefore whether a charitable donation has in fact been made.s

Dinner/Lottery Tickets

Revenue Canada acknowledges that upon the acquisition of a ticket to attend a gala undertaken by a registered charity, the difference between the fair market value of the cost of the event and the purchase price of the ticket will be considered a gift notwithstanding that there has been some consideration received by the donor. For other events, in order to quantify the gift, a deduction is made of the fair market value of comparable events that charge admission or an estimate is made of the fair market value of the services provided. Although this may be applicable to concert tickets and dinner tickets, for example, it will not be applicable to lottery tickets because there is real consideration passing, that is, the opportunity to win the lottery.6 However, if a ticket provides for a dinner event and a lottery is to be held at the event but the acquisition of the dinner ticket is not conditional upon acquiring a lottery ticket, a portion of the dinner ticket would be considered a charitable donation notwithstanding the existence of the lottery.7 Although there is an apportionment for dinner/gala tickets, for example, Revenue Canada in the TiteB case would not allow an apportionment between what is received by way of consideration and what is considered a gift. (The case involved acquisition of a painting from a charity.)

Inducements

In some circumstances charities will provide an inducement of little or no monetary value as an incentive for individuals to make donations. Such inducements may range from pens and pads to media attention honouring the individual. In such circumstances Revenue Canada has indicated that such inducements, having little or no resale value, would not prevent the donor receiving tax credit.

Non-Qualifying Contributions

Certain payments, although made to a registered charity, will not qualify as charitable donations because real consideration for the gift has passed from the charity to the donor. Examples of such payments might be:

(1) payments for daycare or nursery school or admission to a program; (2) gifts that are directed by the donor to a particular person or family (as opposed to a particular program) and that may be considered private benevolence;

(3) payment of membership fees and the right to attend events or receive services that are of material value;

(4) payments for lottery tickets (discussed above);

(5) contributions of services which are not considered property and therefore do not qualify as charitable donations (although nothing precludes the charity from paying for the services and having the person providing the services donate the payment back to the charity, provided there is no obligation to do so);

(6) contributions received by loose collection where the donor cannot be identified;

(7) donations of merchandise that are inventory or otherwise a business expense of the donor; and

(8) donations of old clothes, furniture and items of little value.

Business Expense or Charitable Donation

Where a donation of property has been made and where its cost has been, or should have been, charged as a business expense, no charitable donation will be considered to have been made pursuant to subsection 110.1(1) or 118.1(1). This situation may arise where inventory is transferred from a business to a charity for promotional purposes.

Where an individual makes a cash donation as a charitable contribution, the credit that will be available will be less than if the individual could deduct fully the cost of the donation as a business expense pursuant to paragraph 18(1)(a), an expense incurred for the purpose of earning income.

The issue of whether an expenditure is a business expense or a charitable donation frequently arises in situations where the donors have exceeded 20 per cent of their incomes for charitable contributions. This issue was dealt with in Impenco Ltd. v. MNR.9 In that case the taxpayer corporation, a manufacturer of boxes used in the sale of watches and jewellery, contributed approximately 60 per cent of its income to various Jewish charitable organizations. If the contributions were deemed to be business expenses the entire amount would be deductible from taxable income. On the other hand if the contributions were considered to be charitable donations, the taxpayer would be restricted in making donations to 20 per cent of its income for the year, an amount which it had already exceeded. The taxpayer was successful in arguing that the payments were made primarily for business reasons and that the benevolent undertones were secondary to that business purpose. The taxpayer’s argument was based on the fact that its customers were primarily Jewish, that its products were very similar, if not identical, to its competitors’ and that the taxpayer was relying upon the goodwill generated by its benevolence for the creation of income for its business. A significant factor in the determination of the case appeared to be that the taxpayer’s customers were aware of the charitable contributions and that they testified that it was because of those contributions that they dealt with the taxpayer rather than its competitors.

Provincial Laws

In Ontario, for example, there are provincial statutes which may have an impact on the donation of certain types of property to charities. For example, the Charitable Gifts ActiO provides, inter alia, that any time an interest in a business that is carried on for gain or profit is donated for a religious, charitable, educational or public purpose, the recipient organization shall dispose of that portion of its interest which exceeds 10 per cent. An interest in a business includes the ownership of shares, bonds, debentures, mortgages or other securities based upon any asset of the business. Where the interest was given pursuant to a will, it shall be disposed of within seven years from the death of the testator, subject to extension by court order. Similarly, the Charities Accounting Act 11 provides, inter alia, that land shall only be held for the purposes of actual use or occupation of the land for charitable purposes. Certain public bodies such as universities or public hospitals may hold real property for a charitable purpose upon the terms expressed in a devise, bequest or grant made. In Ontario, the Public Trustee oversees the operation of charities vigilantly.

Gifts Of Capital Property

Without the provisions of subsection 118.1(6), gifts of capital property would have immediate income-tax consequences. Paragraphs 69(1)(b) and 70(5)(a) provide that where gifts of capital property are made, inter vivos or by will, the donor or testator is deemed to have received proceeds of the disposition equal to the fair market value of the property. Paragraph 70(5)(b) provides that if the capital property being donated was depreciable property of a prescribed class, the disposition that occurred on death was for an amount midway between the fair market value of the property and its undepreciated capital cost to the deceased2 Recapture of capital cost allowance, in addition to capital gains, may also arise. The predecessor provision to subsection 118.1(6) (subsection 110(2.2) amended in 1984) provided that an individual could designate an amount but only if the capital property that was donated to the charity was used by the charity in carrying on its activities. The subsequently enacted subsection

118.1(6) contained no such restriction and allows gifts of capital property to be made without any immediate tax consequences to the donor, other than any recapture that may arise on disposition of depreciable property regardless of the use of the property by the charity.

Subsection 118.1(6) provides that where an individual either inter vivos of by will makes a gift of:

(a) capital property to a donee who is described in the definition or “total charitable gifts” or “total Crown gifts” in subsection 118.1(1); or

(b) in the case of an individual who is not a resident, real property situated in Canada to a prescribed donee who provides an undertaking to the effect that the property will be held for use in the public interest, 13

and if the fair market value of the property at that time exceeds its adjusted cost base, then the taxpayer or his or her personal representative may designate in the individual’s income tax return in the year in which the gift is made, an amount not greater than the fair market value of the gift and not less than the adjusted cost base thereof. The amount designated will be deemed to be the taxpayers’ proceeds of disposition of the property for determining their capital gain and the amount of the gift made by them for the purposes of the credit. There is no restriction on the type of capital property donated or the purpose for which it will be used by the charity. Subsection 110.1(3) contains a similar provision for corporations.

A United States resident, for example, who gifts real property and designates an amount pursuant to subsection 118.1(6), may avoid Canadian income tax but United States income tax, gift tax and estate tax considerations will remain. The nonresident must obtain a Section 116 certificate on the disposition of the property.

The amount an individual wishes to designate will be based upon the individual’s particular tax circumstances. For example, taxpayers may not wish to recognize any capital gain because they have previously used their capital gains exemption or have no ability to use the tax credit in that year because their contributions are in excess of 20 per cent of their incomes. If capital losses are present, an amount may be designated that would create a capital gain which would be offset by the losses and therefore allow a greater charitable donation credit to be obtained. Similarly consideration would be given as to how long the credit will have to be carried forward if it cannot be used currently and if the credit can be used in the future at all. If a person died and had no capital gains exemption remaining, had little income in the year of death or in the prior year, and was transferring property to a charity that would be subject to the 20-per-cent limitation rule, a designation under subsection 118.1(6) should be made at the cost of the property. It goes without saying that the lower the designation, the lower the capital gain but, similarly, the smaller the credit that will be available.

Although subsection 118.1(6) will permit an individual to avoid a capital gain on the disposition of depreciable property, recapture of capital cost allowance cannot be avoided, nor can there be a creation of a terminal loss. The minimum elected amount is the capital cost of the property and therefore an election cannot be made at the undepreciated capital cost of the property. This applies similarly to corporations pursuant to subsection 110.1(3).

Consider the following situation:

(1) Mr. X is the owner of shares of a company having a nominal cost base.

The company is the owner of substantial appreciated real estate assets which are capital property to it;

(2) Mr. X wishes to leave the shares and, indirectly, the real estate, to a charity in a manner attracting the least amount of tax.

Mr. X provides in his will that the shares are to be transferred to the charity and the executors designate an amount pursuant to subsection 118.1(6), equal to his adjusted cost base of the shares, therefore no tax would be exigible on his death. Thereafter the directors of the company (now owned by the charity), designate under subsection 110.1(3), a transfer of the real estate at its cost to the charity. Although the transfer of the real estate may result in recapture of capital cost allowance previously taken, no other income tax will be exigible on the transfer. By utilizing the elections, the tax that would otherwise result on the deemed disposition of the shares on the death of Mr. X and the tax arising in the company on the subsequent disposition of the real estate by the company to third parties (other than recapture), are avoided. Once the charity has the real estate transferred to it, it can then sell it to a third party. The fact that the real estate may have a low cost base is not relevant as the charity would not be taxable on the sale.

Consideration might also be given to gifting a portion of a capital property over a number of years in order to extend the ability to have a carry-forward of charitable donations. In addition, if the capital property continued to increase in value before it was all gifted, then a greater charitable donation credit would be available, although additional tax may also arise.

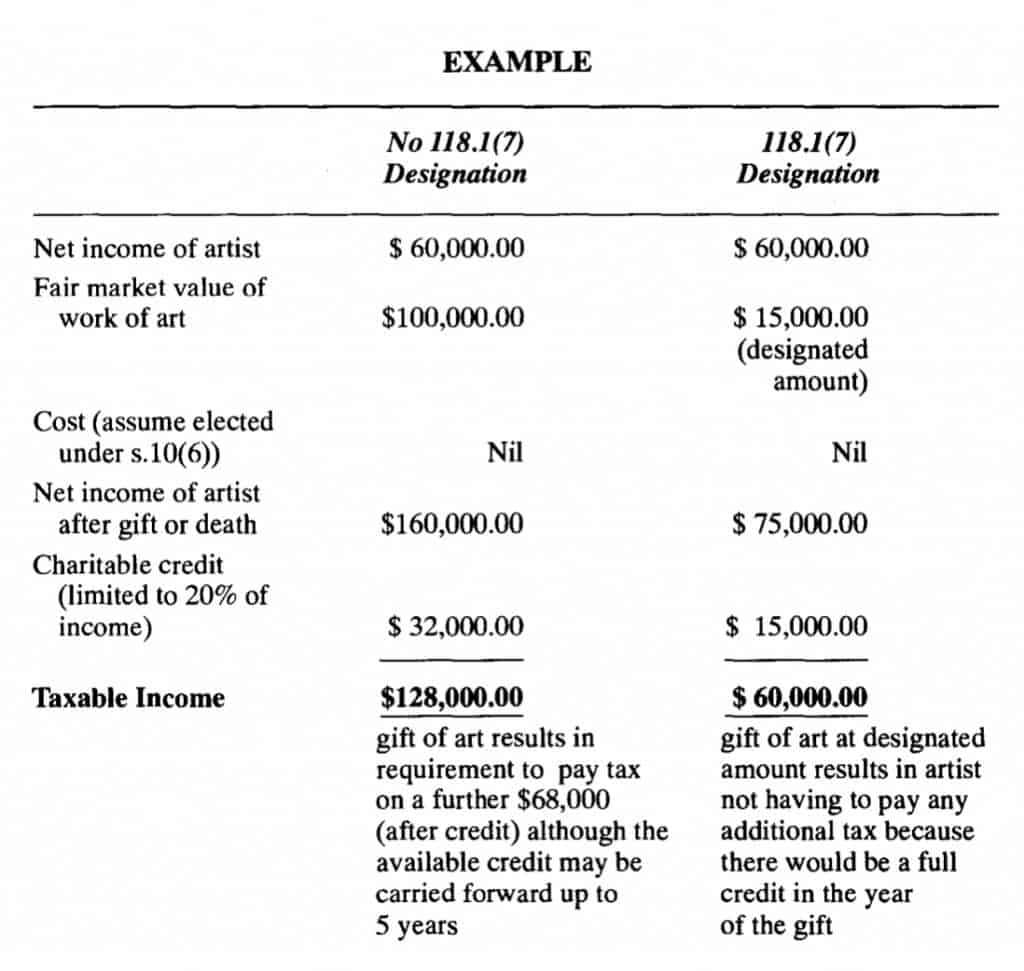

Gifts Of Art By Artists

Subsections 118.1(7) and 118;1(7.1) were enacted to encourage artists to donate their work to galleries and other public institutions without suffering adverse income tax implications. Prior to this enactment, a donation to a charity made by artists of works that constituted part of their inventories would have resulted in a disposition pursuant to paragraph 69(1)(b) and would be fully taxable to the artist, although the artist would be entitled to a tax credit equal to the fair market value of the work. If the artist had previously elected (pursuant to subsection 10(6)) to value the inventory at nil, the amount to be included in income would be greater than the benefit that would be received as a tax credit for the donation, inter alia, because there would be a 20-per-cent limitation on the deduction. Most artists would not have sufficient funds to pay the tax that would result. Similarly, if the artist bequeathed a work from inventory and the artist had previously elected to value it at nil (pursuant to subsection 10(6)) then (pursuant to subsection 70(2)) the value of the work would be included in the artist’s income in the year of death. For donations that fall within the definition of “total cultural gifts”, that is, gifts that are certified by the Canadian Cultural Property Export Review Board, (the “Board”, discussed further on), subsection 118.1(7.1) provides that an artist will be entitled to a credit based upon the fair market value of the donation, as estimated by the Board but, on its disposition, will reflect neither a profit nor a loss for income tax purposes. If the work of art cannot be certified by the Board, by designating an appropriate amount the work of art can be donated without any tax cost to the artist although the credit obtained is equal to the designated amount.

Subsections 118.1(7) and 118.1(7.1) are only applicable on a disposition of a work of art that was part of the artist’s inventory. To the extent that the work of art, gifted or bequeathed, did not form part of the artist’s inventory, there would be a disposition of capital property and a designation under subsection

118.1(6) may be made. This may occur if the artist was donating items that were not in inventory such as manuscripts, diaries, letters or similar capital property. Of course, the artist could use the capital gains exemption to the extent that he or she had not previously done so.

Gifts In The Year of Death And Gifts Of Residual Interests

Subsection 118.1(5) provides that an individual who makes a gift by will to a donee as provided for in subsection 118.1(1), shall be considered to have made the gift in the year of death. To the extent that the amount of the gift cannot be fully used in the year of death, pursuant to subsection 118.1(4) the gift shall be deemed to have been made in the immediately preceding taxation year.14

Gifts of residual interests by individuals are frequently made to provide the deceased with a deduction in the year of death to reduce the income in such year or the previous year, subject to income limitations. Certainly under the succession duty legislation that previously existed in Ontario, it was extremely beneficial to make a residual gift to a registered charity so as to reduce the amount of duty that would be exigible on the estate. Many people feel that the EXAMPLE

present Ontario government may restore succession duties and it may once again prove to be beneficial to take such action.

Where property donated consists of a residual interest in real property or an equitable interest in a trust, the Department considers a gift to have been made15 if the following conditions are met:16

(1) a voluntary transfer of property has occurred;

(2) a vesting of the property has occurred at the time of the transfer; (Vesting will be considered to have occurred if:

(a) the donee of the gift is in existence and is ascertained;

(b) the size of the beneficiaries’ interests are ascertained; and

(c) any conditions attaching to the gift are satisfied.

In other words, absolute ownership cannot be affected by some future event.)

(3) the transfer must be irrevocable;

(4) it must be evident that the charity will eventually receive full ownership and possession of the property transferred.

Creating an equitable interest in a trust, effective upon the transfer of property (including real estate) to an inter vivos or testamentary trust with the proviso that the property be distributed to a beneficiary of the trust (the charity) in the future (for example, when the life interest of the income beneficiary ceases), similarly results in a gift under subsection 110.1(1) or 118.1(3). In both cases, if the conditions noted above are met, then a gift will be considered to have been made at the time of the transfer.

Proposed section 43.117 which deals with dispositions of remainder interests in real property by a taxpayer who retains the life or estate pur autre vie in the property, does not apply where the remainder interest is disposed of to a registered charity that is not a charitable foundation.

In a Technical Interpretation dated October 16, 1989, Revenue Canada considered the provisions of subsection 118.1(5) in the situation of a husband and wife whose wills provided that on the death of one spouse the survivor would receive a life interest in the estate of the other with no power of encroachment on capital. On the death of the survivor, the residue of the estate would be transferred to a registered charity. The husband died and, pursuant to subsection 118.1(5), was deemed to have made a gift of the residue of the estate to the registered charity in the taxation year in which he died. The husband’s personal representatives were able to make the designation provided for in subsection 118.1(6) in his terminal period return. On the death of the surviving wife, the actual transfer of the property to the registered charity would be considered a distribution of property to a beneficiary in satisfaction of the husband’s capital interest. If the trust was a personal or a prescribed trust, pursuant to subsection 107(2) the trust would be deemed to have disposed of its property at its cost amount and the charity would be deemed to have acquired the property at the same amount.

In a further Technical Interpretation dated October 20, 1989, Revenue Canada discussed a similar hypothetical situation except that the personal representatives in the new situation had unlimited power to encroach upon the capital of the spousal trust in favour of the spouse. Because the trustees had the power to encroach upon capital of the spousal trust, the husband would not be considered to have made a gift at the time of his death and therefore subsection 118.1(5) would not be applicable. Revenue Canada has indicated that where a residual interest is not reasonably ascertainable, for example in a situation where a life tenant has rights to encroach upon capital without limitation, no deduction in respect of a charitable donation would be available to the deceased in the year of death. Had the will provided for an encroachment of a specific amount in total or a specific amount in each year, then a calculation could have been made to determine the residual value of the balance of the estate and a deduction would probably have been available.

In the above circumstances, the provisions of paragraph 104(4)(a) and subsection 104(5)18 would apply and the assets in the spousal trust would be deemed to be disposed of at the values indicated in these paragraphs and to be immediately reacquired at the same values. Subsection 118.1(6) could not be used to transfer the assets out of the spousal trust to avoid the deemed disposition on death since it was not the spousal trust that made the donation but the deceased taxpayer by his will. Perhaps if the will were drafted in language broad enough to allow for an unlimited encroachment in favour of the spouse then, although no deduction would be available in the year of death of the testator pursuant to subsection 118.1(5), to the extent that there was in fact an encroachment of all of the trust property in favour of the spouse prior to her death, such spouse could use the provisions of subsection 118.1(6) and gift the property to the charity at the most appropriate designated amount. However it is difficult to know when the spouse will die and therefore to know when the assets should be transferred from the spousal trust to the spouse as an encroachment of capital.

Inter vivos gifts of residual interests are common in situations where works of art are involved and where donors retain possession of the art during their lifetimes although title to the art vests immediately in the charity at the time of the gift. The donor continues to enjoy the property, receives recognition for the gift, and the charity frequently contributes to the cost of insurance, security, and maintenance of the art so as to ensure that it receives the property in question.

Revenue Canada has indicated19 that for the purpose of determining the charitable deduction on the gifting of a residual interest pursuant to subsection 118.1(5), the amount will be determined, inter alia, according to the type of gift made, the interests retained, and the particulars contained in the transfer document used in making the gift. The Department’s approach to determining the value of the residual interest is generally to value the life interest retained by using a formula based upon:

(a) the present fair market value of the whole property; (b) current interest rates;

(c) the life expectancy of any life tenant; and

(d) other relevant factors, and to deduct the amount arrived at using the above formula from the fair market value of the property.

The longer the life expectancy of the life tenant, the smaller the charitable donation will be and the more difficult it will be to establish its value. Since the value of the gift is determined at the time the gift is made, any subsequent increase or decrease in the fair market value of the property gifted does not have an impact on the donor as no additional charitable donation credit is available in the future.

One must also consider the impact of a gift of residual interests on the disbursement quota of a charity. It may be appropriate that such gifts be subject to the 10-year rule20 so that the disbursement quota of the charity is not adversely affected.

Gifts Of Life Insurance Policies

It is becoming increasingly popular for charities to encourage supporters to make them the beneficiaries of new or existing life insurance policies. The donation of a life insurance policy has certain advantages for donors, even if of modest means, enabling them to make substantial gifts to a charity by paying premiums over time which, depending on the age and insurability of the donor, may be quite small. A donor concerned about depleting his or her estate by making a significant bequest to a charity or by probate costs,21 for example, associated with receiving insurance proceeds, will consider a donation of life insurance as an alternative to a cash bequest from the estate after it has received the proceeds from a life insurance policy. The advantage from a charity’s point of view is that a donation of insurance will usually be for a larger amount than a donation of cash. (Experience shows that donors of insurance seldom default on the premiums, particularly if recognition has been received for the gift. Also, experience has shown that payment of the premiums will not usually reduce a donor’s regular gifts to a charity.) One of the disadvantages from the charity’s point of view is that unless the donor has gifted the policy to the charity or made contributions to the charity to pay the premiums, the charity will not necessarily know the amount it will eventually receive nor, in some cases, will it even know of the policy’s existence.

A gift of a life insurance policy to a charity, whether term or whole life, is considered a charitable donation and a credit will be available to the donor within the limits provided for in the Act.22 The donation of an existing policy to a charity will result in a donation equal to the value of the policy (that is the amount by which the cash surrender value of the policy at the time of the donation, if any, exceeds any policy loan outstanding23 plus accumulated dividends and interest) although such donation may result in a disposition pursuant to subsection 148(4) with a resulting inclusion in the donor’s income. The donation of term insurance that has no cash surrender value will not result in a charitable donation at the time of the transfer. When policies are acquired by a donor for a charity, any premium paid to the insurance company at the request of, or with the acquiescence of, the charity is deemed to be a constructive payment to the charity and therefore is considered a charitable donation.24

Similarly, a donation would be considered to have been made when the donor pays an amount equal to the premiums to the charity which, in turn, pays the premiums.

For a donation of insurance to be considered charitable, the life insurance policy in question must be absolutely assigned to the charity and the charity must be the beneficiary of the policy. It is not sufficient for the charity to be named as the beneficiary of the policy. Revenue Canada in a memorandum to the Assessing and Enquiries Directorate dated December 20, 1989, confirmed that where a charity was named as a beneficiary of a life insurance policy, the payment of life insurance proceeds to the beneficiary was merely the fulfilment of a contractual obligation under the policy and was not a gift by the deceased to the beneficiary of the policy and therefore not creditable. If, for example, the policy were a group life policy that could not be assigned or transferred, then no gift could be made as there would be no transfer of property.

As indicated, for a gift to be considered a charitable donation, no benefit or advantage (other than a tax credit) may accrue to the donor as a result of the gift. It is a question whether the donation of a split-dollar life insurance policy would be considered a charitable donation as the donor would probably retain some benefit in such a policy.

Donations of insurance policies to private foundations may be made subject to a direction that the policy or property substituted therefor (and any proceeds received therefrom) be held by the charity for at least 10 years, so that the value of the insurance policy and any proceeds received therefrom would not fall within the disbursement quota of the private foundation as provided for in subparagraph 149.1(1)(e)(i)(B). Premiums paid on the policy should also be subject to a similar direction. If the policy were a single premium policy, not requiring a further premium, any annual accrual of income on the policy would be included in the disbursement quota of the foundation and a TS would be issued for that amount.

Gifts To Acquire Annuities25

Usually when an individual acquires an annuity, the annuity payments received are taxable pursuant to paragraph 56(1)(d) and the capital portion is deductible pursuant to subsection 60(a). If an individual acquires an annuity from a registered charity (assuming that it has the legal capacity to provide such an annuity and the provision of such annuity does not affect its continued registration under the Act)26 and the payment made by the individual for the annuity is in excess of the amount that the individual would expect to receive over the term of the annuity based upon actuarial calculations, the excess amount will be considered a charitable donation. Revenue Canada has indicated in Interpretation Bulletin IT-111R that no portion of any annuity payments received by a taxpayer in such circumstances will be taxable. This position was confirmed by a Technical Interpretation dated June 1, 1989 in which Revenue Canada indicated that even if the individual lived beyond the period during which the annuity payments were expected to be paid and the annuity payments were in excess of the amount expected to be paid, such annuity payments would nevertheless still not be taxable. At the time of the acquisition of the annuity, if the expected annuity payments equalled or exceeded the amount donated, then no charitable donation would be made and the annuity payments would be taxable and a portion deductible as indicated above. However, by a Technical Interpretation dated February 25, 1991, it was indicated that the Department’s administrative policy would not apply where the amount of the annuity payment varied with fluctuations in interest rates as it would be impossible to determine the cost of the annuity and therefore the amount of the donation. In such cases, the usual rules relating to annuities would apply.

To the extent that an individual had not previously used his or her capital gains exemption, or had capital losses, or made an election pursuant to subsection 110.1(6) or otherwise, a transfer of an income-producing property to a registered charity in return for an annuity (if the property has a value in excess of the expected annuity payments) may result in tax-free cash flow to the donor of amounts greater than if the donor merely sold the property and invested the after-tax proceeds.

Gifts Made By A Partnership

Subsection 118.1(8) provides that where an individual is a member of a partnership at the end of its fiscal period, any gift made by the partnership would be deemed to have been a gift made by such an individual in the year in which the fiscal period of the partnership ends. The amount would be equal to the individual’s proportionate interest in the partnership. (A similar provision is contained in subsection 110.1(4) for corporate partners.) The share of the partnership’s income is not reduced by the charitable donation and the share of partnership donations is added to the partner’s other charitable donations in determining the limit, for tax purposes, of charitable donations that could be made during such a year.

Many partnerships will have a fiscal year ending after December 31 in each year so as to defer the recognition of income by an individual who is a partner until the next calendar year. In such circumstances it may be appropriate for the partners to make charitable donations outside of the partnership by taking an extra draw from the partnership, rather than having the partnership make the donation. This would mean the charitable donation is available to the individual partners in the calendar year in which the donation is made and not deferred to be available to the individual partners in the calendar year during which the partnership’s fiscal year ends.

Tuition Fees As Charitable Donations If Paid To A Religious School Generally, tuition fees paid to an educational institution are eligible for credit pursuant to section 118.5 but no receipt may be issued for charitable purposes notwithstanding that the institution may be a charitable organization. To the extent that amounts are paid to a school which teaches religion exclusively or to a school which operates both as a religious and secular school, then the amounts paid for the religious portion of the education would be considered charitable donations rather than tuition fees. Revenue Canada has set out, in Information Circular 75-23, various methods of determining the amount of the charitable donation that may be available with respect to fees paid to a school which teaches both secular and religious subjects.

Gifts By Commuters

Pursuant to subsection 118.1(9), where individuals reside in Canada near the boundary between Canada and the United States and if (a) they commutes to their principal places of employment or business in the United States; and (b) their chief sources of income for the year are their employments or businesses, then any gift made by them in the year to a religious, charitable, scientific, literary or educational organization created under the laws of the United States that would be allowed as a charitable deduction under the Internal Revenue Code, shall, for the purposes of the definition of “total charitable gifts” be deemed to have been made to a registered charity. This is one exception to the rule that only gifts to charities that are qualified donees qualify as charitable donations for tax purposes. Unlike the provisions of Article XXI(6) of the Canada-U.S. Tax Convention (the “Treaty”, discussed further on), the amount of the charitable donations made by such individuals has no bearing on whether such individuals have income from a U.S. source and is only limited by the rules in section 118.1. There is no guidance in the Act or in any jurisprudence as to how near the border an individual must reside and the frequency of attendance in the United States to ensure that the individual is a commuter.

Gifts To United States Charities

In addition to the rules in paragraph 118.1(1)(f) relating to gifts to universities outside Canada or, as provided in subsection 118.1(g), gifts made to charitable organizations outside of Canada where Her Majesty has made a gift, Article XXI(6) of the Treaty provides that gifts by a resident of Canada to an organization resident in the United States which would be exempt from United States tax and which would qualify as a charity in Canada, shall be treated as if the gifts were made to a registered charity in Canada.27

To the extent that a Canadian resident has income from a United States source, gifts to the U.S. charitable organizations noted above will be deductible under Part I of the Act, provided that they do not exceed 20 per cent of U.S.-source income, unless such gifts were made to a college or university in which the resident or a member of his or her family has been enrolled. The amount of the charitable contributions cannot, in any event, exceed 20 per cent of income but any excess can be carried forward in accordance with the normal rules. (Paragraph 5 of the Treaty provides for reciprocal rules for citizens or residents of the United States making gifts to organizations which are resident in Canada.)

Revenue Canada has indicated that the election pursuant to subsection 110.1(3) or 118.1(6) may be made with respect to gifts made to any United States charitable organization that would otherwise qualify pursuant to Article XXI(6) of the Treaty.

For the purposes of paragraphs 5 and 6 of Article XXI of the Treaty, “family” is defined very broadly as meaning an individual, his or her brothers and sisters (whether by whole or half-blood or by adoption), a spouse, ancestors, lineal descendants and adopted descendants. The Treaty also provides that competent authorities of Canada and the United States will determine the eligibility of organizations to receive gifts pursuant to paragraphs 5 and 6.

Gifts To Universities Outside of Canada

Paragraph 118.1(f) provides that gifts made by an individual to a university outside of Canada prescribed to be a university the student body of which ordinarily includes students from Canada, shall be included in the definition of “total charitable gifts”. Section 3503 of Regulation XXXV prescribes numerous universities outside of Canada named in Schedule VIII thereof to be universities the student body of which ordinarily includes students from Canada.

Gifts Made By Her Majesty To Charitable Organizations Outside Of Canada

Donors resident in Canada may make gifts to charities outside of Canada and have them qualify as “gifts” pursuant to subparagraph 110.1(1)(a)(vii) if the donors are corporations or, pursuant to paragraph 118.1(1)(g), if the donors are individuals (including trusts), provided that Her Majesty in right of Canada has made a gift to such a charity. To qualify as charitable gifts, the gifts must be made by an individual or a trust in the calendar year in which Her Majesty made a gift or in the following calendar year. A charitable gift by a corporation or trust which does not report on a calendar-year basis qualifies if made in the taxation year which includes the date of the gift by Her Majesty or within 12 months immediately following the taxation year in which the gift was made.

Similar gifts which have been made by a partnership qualify as a donation of the partners (whether individuals, corporations or trusts) for the periods described above. Information Circular 84-3R4 sets out those organizations to which Her Majesty has made either one-time-only gifts or continuing gifts and the dates of such gifts.

Donations Using Agents

With few exceptions, an individual cannot obtain tax relief for providing funds to a non-qualified donee carrying on charitable activities. However, indirectly, an individual may be able to support what would otherwise be a non-qualified donee by making a donation to a charitable organization in Canada which uses agents to carry on a charitable activity in conjunction with a non-qualified donee. In such circumstances, those activities would be considered an activity of the charitable organization, carried on under its control and supervision. For an agency relationship to be effective, Revenue Canada has indicated that a formal agreement should be entered into that contains the following elements:

1. The non-qualified donee to be funded will be carrying out specific activities which the charitable organization wishes to see accomplished on its behalf.

2. The charitable organization’s funds, held by its appointed agent, will be segregated from those of other project participants so that its role in any particular project will be clearly identifiable as its own charitable activity.

3. The agent provides continuous reporting to the charitable organization concerning the activities which are carried out on behalf of the charitable organization.

Provided that the agency relationship is properly established and maintained, this effectively allows a donor to contribute funds, indirectly, to what would otherwise be a non-qualified donee.

Gifts To The Crown

Paragraph 110.1(1)(b) with respect to corporations and subsection 118.1(1) with respect to individuals, contained in the definition of “total Crown gifts”, provides for a deduction with respect to corporations and a credit for individuals for gifts to Her Majesty in right of Canada and Her Majesty in right of a province. Any such gifts would also include gifts to agents of the Government of Canada or of a province.28 Donors must ensure that the agent in question was an agent of the Crown by reviewing the legislation creating the entity to determine whether it is expressly an agent of the Crown or considered an agent of the Crown in common law.29If what purports to be a gift is really a part of a business transaction, it will be disallowed as a gift to the Crown.30 The Act provides for generous treatment of gifts to Her Majesty. Such gifts will not be subject to the usual tax-credit limitation of 20 per cent of income in each year, and any unused credits may be carried forward for five years.

Gifts Of Cultural Property

The Cultural Property Export and Import Act31(CPEIA), in conjunction with various provisions of the Income Tax Act, is intended to encourage individuals and corporations to donate cultural property to certain designated institutions in Canada. The CPEIA sets out the criteria to be established for property to be certified as an eligible gift and the basis on which institutions may be designated as appropriate recipients for such gifts.

Paragraph 110.1(1)(c) with respect to corporations and subsection 118.1(1) in the definition of “total cultural gifts” with respect to individuals, provides for favourable tax results with respect to gifts which:

(a) meet the objects of the Canadian Cultural Property Export Review Board as determined under the CPEIA in that the gift must have outstanding significance, inter alia, by reason of its association with Canadian history or national life, its aesthetic qualities or its value in the study of arts and sciences and that its loss would significantly diminish the national heritage;

(b) are not considered charitable gifts for purposes of deduction or credit; and

(c) are made to an institution designated under the CPEIA.

Subparagraph 39(1)(a)(i.1) provides that a sale, gift or bequest of certified cultural property to a designated institution will not, notwithstanding the provisions of subsections 69(1) and 70(5), create any capital gain even though the donor is deemed to have received, and is allowed to deduct, an amount equal to the fair market value.32 Any gift by will made by an individual to a donee described in subsection 118.1(1) is deemed by subsection 118.1(5) to have been made by an individual in the taxation year in which he or she died, notwithstanding that the executor may not transfer the property to the donee until after the executor’s year, provided the gift is transferred within 36 months of the death of the taxpayer or such longer period as is reasonable in the circumstances. In addition to the fact that no capital gain will arise, minimum tax will also not arise on the disposition of cultural property to a designated institution.

There are no restrictions on recognizing any allowable capital losses on the disposition of any cultural property except those restrictions related to personal-use property and listed personal property or limitations otherwise set out in the Act. In addition to no capital gain being recognized with respect to the transfer, pursuant to paragraph 110.1(1)(c), and to subsection 118.1(1), a corporation may deduct, and an individual is provided with a credit for, the value of the cultural property disposed of with no 20-per-cent limitation. To the extent that the corporation or individual is not able to utilize the full deduction or credit in the year of the gift, the excess amount may be carried forward for five years. In the year of death, to the extent that the individual cannot fully utilize the credit, the credit may be carried back to the year prior to the year of death with no 20-per-cent limitation.

Revenue Canada’s position is that a disposition of cultural property must be a disposition of the whole of an object and, accordingly, a disposition of a residual interest in an object or a portion of an object will not be considered as a gift of the object for these purposes.33

If the recipient cultural institution disposes of the certified cultural property within five years of certification, it will be required to pay a tax equal to 30 per cent of the fair market value of the property at the time of disposition, unless the disposition is made to another designated cultural institution.34

Gifts If A Vow Of Perpetual Poverty Has Been Taken

Subsection 110(2) of the Act provides that where an individual is a member of a religious order and has taken a vow of perpetual poverty, he or she may deduct from income the aggregate of (1) superannuation or pension benefits, and (2) earned income for the year, if paid to the religious order. Only if all of such amounts are paid to the order, will such an individual qualify for the deduction set out in subsection 110(2). If only a portion of the income is paid, the provisions of subsection 110(2) are not applicable but that portion may qualify as a charitable donation pursuant to subsection 118.1(1). In Interpretation Bulletin IT-86R, Revenue Canada has enumerated other circumstances in which the deduction in subsection 110(2) may not be applicable. By administrative practice, Revenue Canada will also allow any taxable benefit arising pursuant to paragraph 6(1)(a) to be similarly deducted pursuant to subsection 110(2).

Acceleration Of Donations

1. Without Payment of Cash

The acceleration of charitable deduction, without the immediate payment of cash may be desirable, for example, in situations where a charitable deduction could be utilized but no cash is available to make a donation. Consider the following:

(a) Company X controlled by Mr. X has certain real estate which is capital property and which it transfers to its wholly-owned subsidiary (Newco) pursuant to subsection 85(1). Although the transfer would take place at fair market value, the amount elected would be the cost amount (as defined in the Act) of the property transferred so that there would not be any immediate tax consequences.35 The appropriate election form would be filed on a timely basis.

(b) In consideration for the transfer, Newco would provide Company X

with:

(i) a promissory note (Promissory Note) in an amount equal to the cost amount, which Promissory Note would have a term in excess of 19 years and bear interest at a rate equal to the prescribed rate of interest under the Act; and

(ii) for the balance of the purchase price, common shares or special shares of Newco having a fair market value equal to the difference between the fair market value of the property transferred and the fair market value of the Promissory Note in (i) above.

(c) Company X would gift the Promissory Note to a private foundation, for example, as defined in paragraph 149.1(1)(f), subject to a direction to the effect that the Promissory Note, or property substituted therefor, is to be held by the foundation for a period of time in excess of 10 years.

Company X would be entitled, in the year of the gift, to a deduction for the charitable gift pursuant to paragraph 110.1(1)(a) for the principal amount of the Promissory Note, even though the Promissory Note is not due for a period of time in excess of 10 years.

Paragraph 149.1(1)(a) provides that in meeting its disbursement quota, the foundation must disburse, in each year, 80 per cent of the amounts for which the foundation issues a receipt for income tax purposes in its immediately preceding taxation year other than, inter alia, for a gift received subject to a direction that it be held for not less than 10 years. In other words, the foundation would not subsequently be required to disburse 80 per cent of the income derived from the Promissory Note.

The interest paid by Newco on the Promissory Note should be deductible against the income earned from the property transferred to Newco in that the interest expense is being incurred for the purpose of acquiring the asset from Company X.

If the promissory note is gifted and the interest rate is less than the prescribed rate (which presumably is the fair market rate) then the amount of the charitable donation would be discounted by an amount which reflects the fair market value of the Promissory Note. To the extent that the Promissory Note carries a fair market interest, it is not likely that there will be a discount.

The provisions of section 189 could in some circumstances cause a tax to be paid by a taxpayer with respect to non-qualified investments of the foundation. That section indicates that where a debt is owed by a taxpayer (Newco) to a registered charity (the foundation) and the debt is a non-qualified investment of the foundation, the taxpayer will pay a tax equal to the difference between what was being paid on the debt and the lesser of the prescribed rate or the rate that would be paid on such debt had the taxpayer and the foundation been dealing with each other at arms’ length and had the business of the foundation been the lending of money. If such an interest rate is charged on the Promissory Note, the tax will not arise. A non-qualified investment is defined in paragraph

149.1(1)(e.l) as, inter alia, a debt owing to a foundation by a corporation controlled by the members, shareholders, officers or directors of the foundation.

A gift of a Promissory Note in the above circumstances also should not cause difficulties with the Public Trustee as it is a gift of an existing asset that the foundation either accepts or rejects as opposed to a situation where there is self-dealing with the foundation, for example, in circumstances where the foundation receives a cash donation and loans it to Newco.

A calculation must be done to ensure that the deduction received by Company X in the year that the gift of the Promissory Note is made provides sufficient benefit to Company X, as interest will have to be paid on the Promissory Note in each year that it is outstanding and the Promissory Note will ultimately have to be paid, with no further charitable deduction being available when it is paid. If life insurance could be acquired by Company X on the life of Mr. X, at an affordable rate, funds may be available in this way to repay the Promissory Note.

Similar planning can be undertaken with respect to a public foundation.

2. Choosing a Fiscal Year End for a Private Foundation

Mr. X could accelerate his donations in a year, for example, by donations made to a private foundation which he establishes and which has a November 30 year end. Mr. X could make substantial charitable donations to the foundation in late December and thereby receive an official receipt for the donations in the calendar year in which they were made. The foundation would not be required to disburse such funds until its following year. Mr. X has the luxury of time in determining where the donations will ultimately go although he will already have received a credit for the donations. Mr. X may not be aware of the extent of his income until late in the calendar year and if he had to determine all of the charities which he wishes ultimately to benefit, it may very well be that he would not make such donations in that calendar year, but would wait until the next year. The use of a private foundation in such circumstances will allow Mr. X to accelerate the credit for the donation.

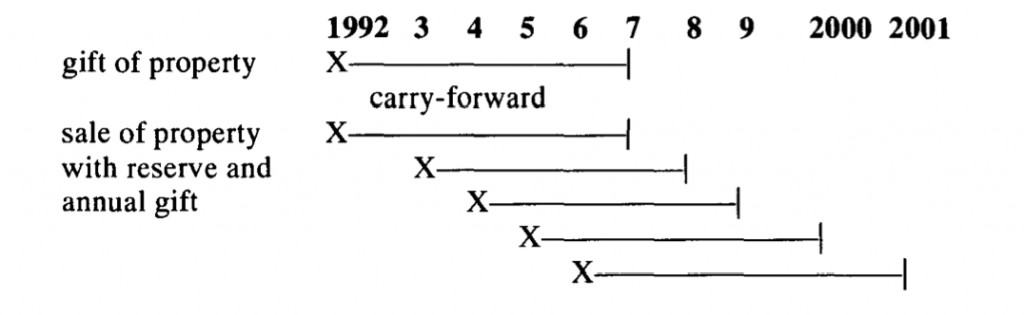

Extension of Donation Carry-Forward

If a donor will not be able to utilize the credits received on a donation within the five-year carry-forward period, then a sale of property, rather than a gift of same should be made. Consider the following:

1. Mr. X sells capital property he owns to a charity and in consideration for the transfer receives a promissory note equal to 4/Sths of the purchase price which is due in equal instalments over the next four years after the year of the gift. Mr. X takes a reserve on the sale pursuant to subparagraph 40(1)(a)(iii). Mr. X has made a charitable donation equal to 1/Sth of the value of the property in the year of the sale.

2. Mr. X makes a donation to the charity in each year of an amount equal to what would be due under the promissory note and obtains a credit for a charitable donation equal to the gift.

3. The charity pays the amount due on the promissory note in each year. Mr. X has effectively gifted the property to the charity and has created a five-year carry-forward for the cash donations that he makes in each year,

rather than only having available to him a five-year carry-forward from the date of the initial gift. The difference in carry-forwards may be illustrated as follows:

FOOTNOTES

1. Except as otherwise noted, all references throughout are to the Income Tax Act, S.C.

1970-71-72, c.63 as amended. This paper was originally based on a program prepared for The Canadian Bar Association on October 16, 1990 and entitled “Charities and The Tax Man and More”.

2. The administrative position of Revenue Canada, as set out in Interpretation Bulletin IT-62, is that a Native Peoples’ band council would be considered a Canadian municipality for the purpose of credits for charitable donations where the band council has actively enacted at least one bylaw under sections 81(which provides for bylaws for such matters as regulation of traffic and the observance of law and order) and 83 (providing for taxation of land and licensing for businesses) of the Indian Act relating to the reserve.

In a Technical Interpretation dated February 17, 1992, the Department indicated that consideration of $1.00 paid for a transfer of real property to a Canadian municipality, which property had a substantial fair market value, and for which $1.00 was paid merely as a formality under land transfer tax legislation, did not cause the transfer to be considered other than a gift. Although a gift is a gratuitous transfer of property, where no consideration is received, the Department has indicated in Interpretation Bulletin IT-110R2 that if an inducement of little or no value is offered for a gift, the status of the gift is not affected.

3. Memorandum, Business and General Division, Revenue Canada Taxation, April 1O, 1991.

4. Technical Interpretation, Revenue Canada Taxation, July 13, 1990.

5. See for example, Burns v. The Queen 90 DTC 6335 (FCA); The Queen v. McBurney 85

DTC 5433 (FCA); and Tite v. MNR 86 DTC 1788 (TCC). These cases establish that an essential element of a gift is the donor’s awareness that no consideration will be received.

6. Revenue Canada has indicated in a Technical Interpretation dated November 26, 1990 that if a ticket holder has agreed in advance to gift the prize to the charity if he wins it, the fair market value of the chance to win (as represented by his individual ticket) would be considered a charitable donation regardless of whether the individual wins the prize or not.

7. Paragraph 14 of Interpretation Bulletin IT-110R2 sets up the Department’s view that it is possible for a donor both to make a purchase from a charitable organization and to make a gift, provided they are two separate transactions, independent of each other.

8. Tite, supra, footnote 5.

9. 88 DTC 1242 (TTC). See also Olympia Floor & Wall Tile (Quebec) Ltd. v. MNR 70 DTC

6085 (Ex. Ct.).

10. R.S.O. 1990, c.C.8, s. 2 and 3.

11. R.S.O. 1990, c.C.lO, s. 6b and 6c.

12. Technical amendments proposed on December 20, 1991, will eliminate this midway point rule with respect to depreciable property so that for dispositions occurring after 1992, depreciable property will also be deemed to be disposed of at fair market value.

13. Administratively, the charity would provide a letter to donors to be attached to their return setting out (1) the date of the gift; (2) a description of the property; (3) name and address of donor; (4) name and address of appraiser; and (5) a description of the uses to which the property would be put so as to support the contention of the charity that the property was to be held in the public interest.

14. Administratively, the Department will allow a surviving spouse to claim a tax credit in the year of death of the deceased spouse in respect of a gift which was bequeathed by the deceased’s will.

15. See 0’Brien Estate v. MNR, 92 DTC 1349 (TCC) wherein the Court provided that a residual gift is properly deductible (under the predecessor subsection 110(2.1)) even if no receipt was issued by the registered charity because it had not yet received any tangible gift.

16. Interpretation Bulletin IT-226R.

17. A Notice of Ways and Means Motion to Amend the Income TaxActwas tabled in the House of Commons on June 19, 1992, incorporating the Technical Amendments proposed in the draft legislation was released on December 20, 1991.

18. Ibid., relating to the disposition of depreciable property.

19. Ibid.

20. See clause 149.1(1)(e)(i)(B). This clause excludes from the “disbursement quota” of a charitable foundation, a gift of capital received by way of bequest or inheritance. For this purpose, Revenue Canada has indicated that the term “capital” should be interpreted narrowly to be “capital” as opposed to “income”. Therefore, if a foundation receives a bequest forming a portion of the income of an estate, the gift would not be excluded from the disbursement quota as a result of the above, but may be excluded if no receipt is issued and would also be excluded from the income of the foundation by virtue of clause

149.1(12)(b)(ii)(A).

21. On June 8, 1992, probate fees in Ontario increased threefold for estates valued in excess of

$50,000, to $15 per $1,000 of assets.

22. Interpretation Bulletin IT-244R3.

23. Any subsequent payment of the policy loan will constitute a charitable donation.

24. See Konrad v. MNR 75 DTC 199 (TRB).

25. See The Queen v. Rumack 92 DTC 6142 (FCA) where an annuity was acquired as a prize in a lottery.

26. Revenue Canada has taken the administrative position in paragraph 2 of Interpretation Bulletin IT-111R that a charitable organization as defined in paragraph 149.1(1)(b) may issue an annuity without affecting its registration under the Act but that a charitable foundation as defined in paragraph 149.1(1)(a) may not, because the issuance of an annuity would be considered the incurring of a debt for a purpose other than the purposes referred to in subsection 149.1(3) and (4) and therefore would make the foundation subject to deregistration.

27. Paragraph 1 of Article XXI of the Treaty provides, inter alia, that income derived by a charitable organization resident in the United States is exempt from tax in Canada to the extent that it is exempt from tax in the United States. Paragraph 76 of Information Circular

77-16R3, sets out an administrative procedure under which an organization resident in the United States may obtain a certificate to the effect that it qualifies for this exemption. Paragraph 76(g) of 77-16R3 states that a canadian resident paying income to a United States organization to which a certificate has been issued is not required to withhold Part XIII tax from these payments.

28. See for example, the University Foundations Act and the Hospital Foundation Act (British Columbia) and An Act Respecting University Foundations (Ontario) (given Royal Assent November 5, 1992). [See also “Parallel Foundations and Crown Foundations”, pp. 37-52.]

29. See Murdoch v. MNR 79 DTC 206(TRB).

30. See Hudson Bay Mining and Smelting Co. Limited v. The Queen 89 DTC 5515 (FCA). (Leave to appeal to S.C.C. denied.)

31. R.S.C. 1985, c.C-51.

32. See The Queen v. Albert D. Friedberg 92DTC 6031(FCA); (leave to appeal to the SCC denied). See also H. Erlichman, “Case Comment: Profitable Donations-What Price Culture?” (1992), 11 Philanthrop. No.2, p. 3 and McDonnell, T.E., “GAAR & Pre-September 13, 1988 Tax Planning: Part I- The Charitable Deduction Issue” (1989), 37:2 CTJ

408 for discussions of the Friedberg case.

In a memo dated September 25, 1989, the Business and General Division of Revenue Canada has indicated that the GAAR Committee expressed the view that arrangements that circumvent charitable donation limitations in paragraph 110.1(1)(b) and subsection

118.1(1) would not be subject to the application of the provisions of subsection 245(2). There is no indication as to why Revenue Canada took that position.

The Canadian Cultural Property Export Review Board and the Appraisal Section of Revenue Canada have confirmed that appraisals of art are made on a piece-by-piece basis and each painting or work of art is appraised at fair market value with little or no consideration given to premiums or discounts for the fact that the art may or may not be in a collection.

33. Paragraph 12, Interpretation Bulletin IT-407R3.

34. Section 207.3.

35. In Ontario, land transfer tax may also be avoided in some circumstances.

MAXWELL GOTLIEB

Cassels, Brock & Blackwell, Barristers and Solicitors, Toronto