Introduction Significant changes have been made in the taxation of charities for 1977 and subsequent taxation years. Thes.e changes were designed to prevent the abuse by charities of their special status and many charities may find them restrictive. The penalty for failing to follow the new rules can be severe.

Registration The new rules apply to all charities and in the new system all charities must be registered with Revenue Canada in order to be exempt from taxation. Prior to 1977, a charity was required to be registered only if it wished to issue tax receipts for donations. Although many charities will have been registered already in order to issue these receipts, if the charity is not registered, it will have to take the appropriate steps to do so now if it wishes to be exempt from income tax.

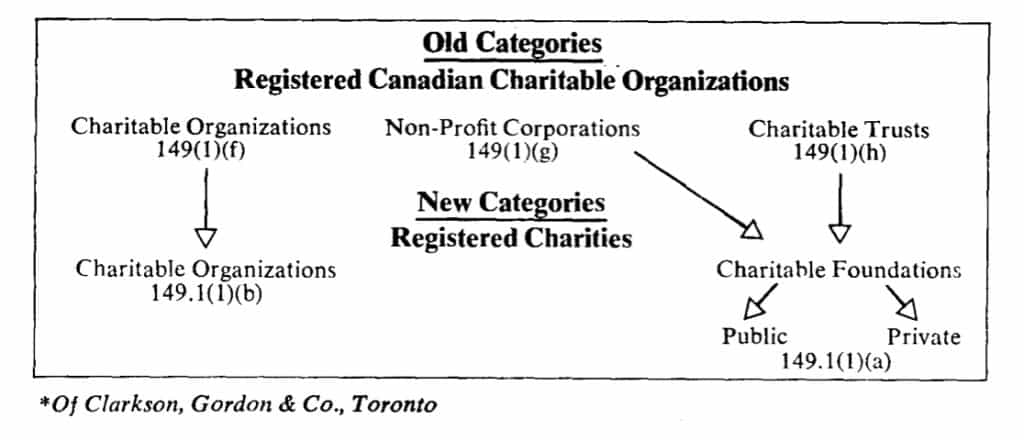

Categories of Charities In the old system, there were three categories of charities -charitable organizations, non-profit corporations and charitable trusts and each of these terms had a specific meaning in the Income Tax Act. Frequently the term “charitable organization” was also used in a general sense to describe a charity of any of the three categories. The problem with this classification system was that it did not distinguish the two fundamental types of charities -those which do the charitable work themselves and those which raise the funds for other charities.

The new classification system recognizes this distinction and there are now two main categories, charitable organizations which carry on charitable work directly and charitable foundations which largely give to others. Foundations can be public or private and this aspect is discussed later in this article. The relationship between the old system and new system is shown in the following illustration.

Usually a charity that was a charitable organization as defined in paragraph 149(1)(f) in the old system will continue as a charitable organization under the new rules. However, some care must be taken where the activities of the organization have changed substantially since initial registration. In particular, consideration must be given to the use of its income as discussed below.

A charity that was a non-profit corporation or a charitable trust under the old rules will become either a charitable organization or a charitable foundation depending on how much of its income is used in direct charitable activity and how much is disbursed to other groups (“qualified donees” defined below).

Generally, the Department will consider that disbursements in excess of 50% of the income for the year to qualified donees will mean that the organization is a foundation for that year. This indicates that the category of a charity can change from year to year.

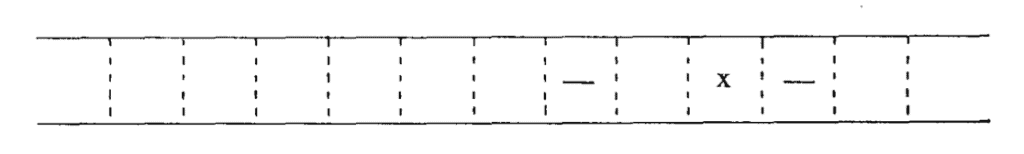

Many charities which were registered under the old system are not certain how they were classified originally. One method of checking this is by referring to the official registration number. This number should have the following form:

The third number from the right indicated as “x” is the code number. If this number is “3”, the charity has been registered as a non-profit corporation under paragraph 149(1)(g); if “5”, as a charitable trust under paragraph 149(1)(h); and if any other number, as a charitable organization under paragraph 149(1)(f). This is only a check on how the organization was initially registered in the old system and is not necessarily relevant in the new system.

When are the New Rules Effective?

The new rules will be applicable to the 1977 and subsequent taxation years. There are a number of transitional rules which will limit the impact of the new requirements for the first few years in the new system. Every charity will have to examine its operations to ensure that when the system is mature no problems arise. This planning should be done now and not when the transitional years have passed. It should also be noted that some tests are based on what has happened in the immediately preceding taxation year.

The Main Problem: Revocation Failing to meet the new requirements can result in the revocation of the registration of the charity. The penalty tax which is imposed following revocation is severe and would mean the end of that particular charity. The tax is equal to the fair market value on the day on which revocation is effective of all the assets of the charity that have not been transferred within one year to another registered charity or qualified donee (a proposal in the 1977 federal budget would change the day to the date that notice of revocation is mailed by the Minister). Amounts paid by the charity after the day of revocation in respect of bona fide debts that were outstanding on that day and amounts paid for reasonable expenses within the one year period are also deducted from the tax. There is a provision to prevent the transfer of any amounts to another person other than in accordance with the Act.

No charity should assume that such a step would never be taken against it. Revocation does happen and will continue to happen.

What Could Cause Revocation?

Some of the reasons that could lead to revocation are the same for each category and some apply only to a particular category of charity.

1. All registered charities

Any registered charity can lose its registration for any of the following reasons (reasons for revocation of specific categories of charities are discussed later in this article):

(a) The registered charity applies to the Minister in writing for revocation of its registration.

(b) The registered charity ceases to comply with the requirements of the Income Tax Act for its registration. This means that the entity ceases to be a registered charity as defined. In the new system, a registered charity must be resident in Canada and be created or established in Canada.

(c) The registered charity fails to file an information return as and when required. In the past, all registered charities had to file an annual return of information (form T2052) with a copy of the financial statements within three months from the end of each fiscal period. The new rules require the filing of a yearly information return (form T2052, revised 1977) and a public information return (form T3010) within three months from the end of each taxation year. The information in the public information return can be communicated to the public by the Minister.

As a matter of interest, it should also be noted that any charity that is constituted as a corporation should file an annual federal income tax return unless specific exemption has been granted by the Department. Normally, all that is required on the return is basic information such as the name and address along with copies of the financial statements.

Where applicable, Quebec also requires a separate return but Ontario only requires a return if the corporation is liable for provincial income taxes or is asked in writing to file.

(d) The registered charity issues a receipt for a gift or donation otherwise than in accordance with the Income Tax Act and the regulations or that contains false information. Although this situation may appear obvious it should be noted that the regulations describe in detail the contents of receipts.

(e) The registered charity fails to comply with or contravenes section 230 or 231 of the Income Tax Act. These two sections deal with keeping books and records and investigation provisions. With respect to section 230, the charity must keep records and books of account (including a duplicate of each receipt containing prescribed information for a donation received by it) at an address in Canada recorded with the Minister or designated by the Minister in such form and containing such information as will enable the donations to it that arc deductible under the Act to be verified.

It is important that the Minister always have the current address of the charity and whenever the address of the charity changes, the charity should inform the Department. This will enable the Department to contact the charity quickly if additional information is required.

2. Charitable organizations

This section is applicable to charitable organizations (as defined). Reference should also be made to the points listed above which apply to all registered charities.

(a) Definition

A charitable organization is defined as “an organization, whether or not incorporated, all the resources of which are devoted to charitable activities carried on by the organization itself and no part of the income of which is payable to, or is otherwise available for, the personal benefit of any proprietor, member, trustee or settlor thereof”. These organizations carry on the direct charitable activity themselves and may also raise their own funds. This is opposed to raising funds for other charities. While no part of the income may be made available for the personal benefit of any proprietor, member, shareholder, trustee or settlor thereof, the definition does not preclude paying reasonable salaries or other remuneration for legitimate services rendered to the organization.

(b) Disbursements to other charities

In addition to carrying on a direct charitable activity, by definition devoting resources to charitable activities also includes carrying on a related business and disbursements to qualified donees. Carrying on a related business is discussed below. A qualified donee is defined as a donee described in any of subparagraphs 110(1)(a)(i) to (vii) or paragraph 110(1)(b) of the Income Tax Act. Generally, such donees will be registered charities. There is a limit on how much the charitable organization can disburse in this manner. If the donee is not associated with the charitable organization, the limit is 50% of income for that year. If the donee is a registered charity that the Minister has designated in writing as a charity associated with it, there is no limit.

Where two charities have substantially the same charitable aim or activity, it may be advisable to apply for designated status. This will allow greater freedom in transferring funds. Where there is no association, some care must be taken because it is frequently difficult to determine what 50% of the income for the year will be.

(c) Related business

The new rules introduced two new specific situations which can lead to revocation for a charitable organization. The first is the carrying on of a business that is not a related business of that charity and the second is a disbursement test based on receipts issued.

The restriction on the carrying on of a business is an attempt to prevent the giving of an unfair advantage to tax-exempt businesses when they compete with non-exempt businesses. In the past, it was the Department’s practice to allow certain business activities if they were reasonable in nature and scope. Now, however, there is a distinction between related and unrelated business and the Department might take a closer look at these activities. “Related business” is defined to include a “business that is unrelated to the objects of the charity if substantially all of the people employed by the charity in the carrying on of that business are not remunerated for such employment”.

Apart from this provision, there is still very little available on what is meant by “related business”. In the discussion paper, The Tax Treatment of Charities, tabled with the June 23, 1975 budget, the following comments were made regarding carrying on a business:

“The government recognizes that many registered charities do have good reasons for carrying on a business. An art gallery may have a gift store. A hospital may have a cafeteria for visitors. Certain groups sell used clothes and other items. In recent years, the law has been administered to allow such enterprises if the business is directly related to the charitable activity of the organization.

It is proposed to amend the Income Tax Act to allow both charitable organizations and public foundations to carry on a business related to the primary charitable activity. This provision would make clear that the test would not be the fact that the income earned by the business is used for charitable purposes, but rather that the business is a usual and necessary concomitant of the charitable activity.”

A potential problem in this area is that the meaning of related business might be narrowed by the courts, and there is always the possibility that Departmental practice may change over the1 years. If a narrow interpretation of related business does develop, many of the current activities of charitable organizations in Canada may fall under “unrelated business”. This particular area will have to be watched carefully over the next year or two to ascertain if there is any trend in Departmental practice. Universities in particular will have to monitor this because they are often involved in many operations.

(d) Distribution requirement

The second new situation that can lead to revocation for a charitable organization is the failure to meet the distribution requirement. It was mentioned above that a charitable organization must devote all of its resources to charitable activities. This will also have to be kept in mind when making distributions. In addition to this general requirement, there is a specific requirement based on amounts for which certain receipts were issued. The receipts are those which allow the donor to deduct the amount in computing his taxable income (i.e. receipts described in paragraph 110(1)(a)). The charitable organization must expend in a taxation year on charitable activities carried on by it and by way of gifts made by it to qualified donees at least 80% of the amounts for which it issued these receipts in its immediately preceding taxation year (referred to as “receipted income”). The distribution rule based on issued receipts is an attempt to keep fund-raising and associated costs reasonable.

There are a number of points which should be noted with respect to this requirement. The 80% applies to the mature system and transitional rules are available. The relevant percentages are 50% where the immediately preceding taxation year is 1976, 60% where the immediately preceding taxation year is 1977, 70% where the immediately preceding taxation year is 1978 and 80% where the immediately preceding taxation year is a year after 1978. The taxation year of a registered charity is a fiscal period. The amount must be “expended” and this means “paid out” in the year.

A limited three-year carry-forward is available where an excess amount is disbursed in one year. The excess is defined as the amount disbursed in a year in excess of the amounts for which it issued receipts (not amounts in excess of the percentage it is required to disburse). For the carry-forward to be effective prior approval must be obtained in writing from the Minister. There is also a limited averaging provision available which may allow the organization to take an average of the amounts it has disbursed over a period which includes the current year and up to the four preceding years when determining compliance with the distribution requirement.

Finally, the organization may get permission to accumulate funds for a particular purpose. For instance, the charity may be planning a new building and may wish to save funds for that purpose. This permission must be obtained in writing from the Minister and must be for a particular purpose. The Minister may impose certain conditions on the accumulation.

Although permission may be granted in certain situations, many charities will wish to accumulate funds to meet future operating emergencies and may not have the required “particular purpose”. It is possible in this type of situation that permission to accumulate would not be given.

It should be noted that there are no exceptions to the distribution requirement for charitable organizations with respect to the donation itself. As long as a receipt described in paragraph 110(1)(a) was issued, the amount must be included for the test; however, for a public charitable foundation a donation subject to a direction that the property given be held for at least tn is excluded.

3. Charitable foundations-definitions

This section is applicable to charitable foundations. Reference should also be made to the section above which applies to all charities.

A charitable foundation is defined as a “corporation or trust constituted and operat:d exclusively for charitable purposes, no part of the incomof which is payable to, or is otherwise available for, the personal benefit of any proprietor, member, shareholder, trustee or settlor thereof and that is not a charitable organization”. The main function of these organizations is that of raising funds for other charities and they generally do not involve themselves in direct charitable activity.

Charitable purposes include the disbursement of funds to qualified donees (i.e. a donee described in any of subparagraphs 110(1)(a)(i) to (vii) or paragraph 110(1)(b)). The requirement that no part of the income be payable to or available for personal benefit does not precluda reasonable salary or other remuneration for legitimate services rendered to the foundation. These expenses must be reasonable.

It is necessary to distinguish those foundations which are public and those which are private. The new rules differ for each and it is very important to determine if the particular charitable foundation is public or private. A “public foundation” means a “charitable foundation of which more than 50% of the directors or trustees deal with each other and with each of the other directors or trustees at arm’s length, and not more than 75% of the capital contributed or otherwise paid in to the foundation has been so contributed or otherwise paid in by one person or by a group of persons who do not deal with each other at arm’s length”.

A private foundation is a charitable foundation that is not a public foundation. If certain conditions are met, a private foundation may apply to the Minister to be designated as a public foundation. The rules for a private foundation can be more restrictive and so it may be advisable to consider applying for designation as a public foundation. One example given in the discussion paper, The Tax Treatment of Charities, is a foundation which received all of its initial funding from one person but subsequently receives additional funds from other sources who are at arm’s length from the initial donor. It is implied that the foundation must have wide public support before public designation would be given by the Minister.

4. Public foundations

A public foundation might have its registration revoked by the Minister if it carries on an unrelated business, fails to meet a disbursement test, acquires control of any corporation or incurs certain debts.

(a) Related business

Carrying on business is discussed above under charitable organizations and the same comments apply here.

(b) Disbursement requirement

The disbursement test for a public foundation requires that at least the greater of two amounts must be expended.

The first amount is based on amounts for which certain receipts were issued. The receipts are those which allow the donor to deduct the amount in computing his taxable income (i.e. receipts described in paragraph 110(1)(a)). The public foundation must expend in a taxation year on charitable activities carried on by it and by way of gifts made by it to qualified donees at least 80% of the amounts for which it issued these receipts in its immediately preceding taxation year.

There are a number of points which should be noted with respect to this calculation. The 80% applies to the mature system and transitional rules are available. As with charitable organizations, the relevant percentages are 50% where the immediately preceding taxation year is 1976, 60% where the immediately preceding taxation year is 1977, 70% where the immediately preceding taxation year is 1978, and 80% where the immediately preceding taxation year is after 1978. The amount must be “expended” and this means “paid out” in the year. Unlike a charitable organization, a public foundation need not include those gifts received which must be held by it for a period of ten years or more and there is no three-year carry-forward provision for any excess amounts disbursed. As with charitable organizations, limited averaging is available which may allow the foundation to take an average of the amounts it has disbursed over a period which includes the current year and up to the four preceding years when determining compliance with the distribution requirement.

As with charitable organizations, the foundation may get permission to accumulate funds for a particular purpose. The permission must be obtained in writing from the Minister and must be for a particular purpose. The Minister may impose certain conditions on the accumulation.

The second amount which must be determined is based on income. This income distribution test requires the foundation to expend at least 90% of its income for the year.

There are also a number of points which should be noted with respect to the income test. Income means “net income” and should be calculated in the same manner as for any taxable entity. All gifts must be included in computing income except the following:

1. any gift received subject to a trust or direction to the effect that the property given, or property substituted therefor, is to be held by the charity for a period of not less than ten years;2. any gift or portion of a gift in respect of which it is established that the donor is not a charity, and

(a) has not been allowed a deduction under paragraph 110(1)(a) in computing his taxable income, or

(b) was not taxable under section 2 for the taxation year in which the gift was made;

3. any gift or portion of a gift in respect of which it is established that the donor is a charity and that the gift was not made out of the income of the donor.

Because “income” means “net income”, the expenses incurred to earn this income can be deducted. These expenses would include certain salaries, administration and overhead costs incurred to earn this income but would exclude the cost of the charitable activities. Income will include investment income since the calculation is to be made in the same manner as any taxable entity. One exception exists and that is that income for purposes of the distribution requirements that refer to a percentage of incomes and losses will not include taxable capital gains and losses. It should also be noted that the 90% requirement refers to “income” and not “taxable income”. This would appear to require that dividends from taxable Canadian corporations be included. However, a charitable trust that is a registered charity is not required to include the gross-up in income because no offsetting credit would be available. Unlike other tests, no averaging provisions or transitional rules are available. However, there is a limited three-year carry-forward provision applicable to the income test, similar to that described above for the distribution requirements applicable to charitable organizations. In this case, the excess is the amount expended exceeding its income for the year.

The reserve system in force for 1976 and prior taxation years continues and this allows some flexibility for the charity in determining compliance with the income distribution test. It allows a charitable foundation to deduct, in computing its income for the current year, any amount up to the amount of its income for the preceding year, but the foundation must include in income any such amount deducted from income in the preceding year. A special reserve is available in the first year of operations. Finally, as with the other tests, a charity may get permission to accumulate funds.

(c) Control of other corporations

A foundation may not acquire control of any corporation after May 31, 1950. The foundation is deemed not to have acquired control, if it did not purchase or give consideration for any of the shares in the capital stock of the corporation. It sometimes happens in the distribution of an estate that shares are gifted to a foundation. This would not be considered an acquisition of control but there might be a problem with unrelated business if the foundation then operated the company. In addition, certain provincial statutes (for example, The Charitable Gifts Act in Ontario) may impose restrictions on charities limiting the extent to which a charity can hold an interest in a business.

(d) Debts

A foundation may not incur debts after May 31, 1950 other than debts for current operating expenses, debts incurred in connection with the purchase and sale of investments and debts incurred in the course of administering charitable activities.

It was mentioned above that a private foundation may apply to the Minister for public foundation status. If at the time it was a private foundation, it took any action or failed to expend amounts such that the Minister was entitled to revoke its registration as a private foundation, the Minister may, within two years, still revoke its registration even though it subsequently became a public foundation. The requirements for revocation differ for public and private foundations and this clarifies the Minister’s position where such a change in status has taken place.

5. Private foundations

The registration of a private foundation may be revoked if the foundation carries on any business, fails to meet a disbursement test, acquires control of any corporation or incurs certain debts.

Although charitable organizations and public foundations are permitted to carry on a related business, a private foundation may not carry on any business at all.

The comments made for public foundations on acquiring control of any corporation or incurring certain debts are also applicable here.

A private foundation must expend an amount at least equal to its disbursement quota for that year. In simple terms, the foundation must determine three amounts. The first is 5% of the fair market value of certain capital properties, the second is the income derived from those properties and the third is the total income of the foundation. The foundation must expend an amount at least equal to the aggregate of:

(i) the greater of 5% of the fair market value of the capital properties and

90% of the income derived from those properties, and

(ii) 90% of the amount by which the total income of the foundation exceeds the income derived from the properties in (i).

Although the meaning of “capital properties” is not yet clear, certain properties are excluded. These are:

(i) qualified investments of the foundation

(ii) capital properties used directly by the foundation in charitable activity or in the administration of the foundation

(iii) property accumulated with permission of the Minister.

Qualified investments are defined in paragraph 149.l(l)(i) of the Act. It should be noted that reference is made to a share in the capital stock of a public corporation, or a bond, debenture, note or similar obligation of a corporation the shares of which are listed on a prescribed stock exchange in Canada. Shares of a private corporation and shares of U.S. corporations are not qualified investments.

Capital properties used directly by the foundation in charitable activity and administration should not be difficult to identify and are excluded from the test. As with the other tests, permission to accumulate property may be obtained and this property is also excluded.

The 5% figure used in the calculation of the disbursement quota applies to the mature system and transitional rules are available for the 1977 and 1978 taxation years. For 1977 taxation years commencing in 1976, zero per cent is used, for 1977 and 1978 taxation years commencing in 1977, 3 per cent and in respect of all other 1978 taxation years, 4 per cent.

In the calculation of the disbursement quota, the comments with respect to “income” in the public foundation discussion also apply. There is no transitional rule available for the 90% of income portion of the test. However, as with public foundations, there is a limited three-year carry-forward provision applicable to this part of the calculation, similar to that described above.

Conclusion

Although only a small percentage of charities might have abused the special status enjoyed by charities, the new rules designed to stop this abuse will apply to all charities. Many legitimate charities will find that their current activities and actions will have to be reviewed in light of these new restrictions. The penalty that can be applied for failing to abide by the rules can mean the end of the organization and a great deal of care must be exercised.

D. C. BROWN, C.A., Of Clarkson, Gordon & Co., Toronto